1199 PLAZA

1199 Plaza from the East River. Credit: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, photograph by G. E. Kidder Smith.

1199 Plaza

Date: 1975

Architect: Hodne/Stageberg Partners

Address: 2100-2110 First Avenue

Use: Residential

1199 Plaza is a bulky brown brick apartment complex on the border of East Harlem and the Upper East Side facing the East River. It was envisioned as an urban renewal project that would break away from the previous tower in the park developments that occupy much of its surrounding East Harlem neighborhood and the East River waterfront on the Lower East Side. In 1963 a design competition called for the redevelopment of twelve industrial blocks along the East River bounded by 107th and 111th streets between the FDR Drive and First Avenue. The competition specified 1,500 units with 8,000 square feet of community space, 30,000 square feet of retail and 750 parking spots. The winning entry, designed by Thomas Hodne, was inspired by urbanist and writer Jane Jacobs' call for density within the already existing street grid, rejecting tower in the park superblocks. Hodne's initial entry proposed five to six story buildings in a street grid with four 22-story towers along the water. Green space between the buildings and along the waterfront hoped to give the development a human scale while intertwining it into the surrounding urban fabric.

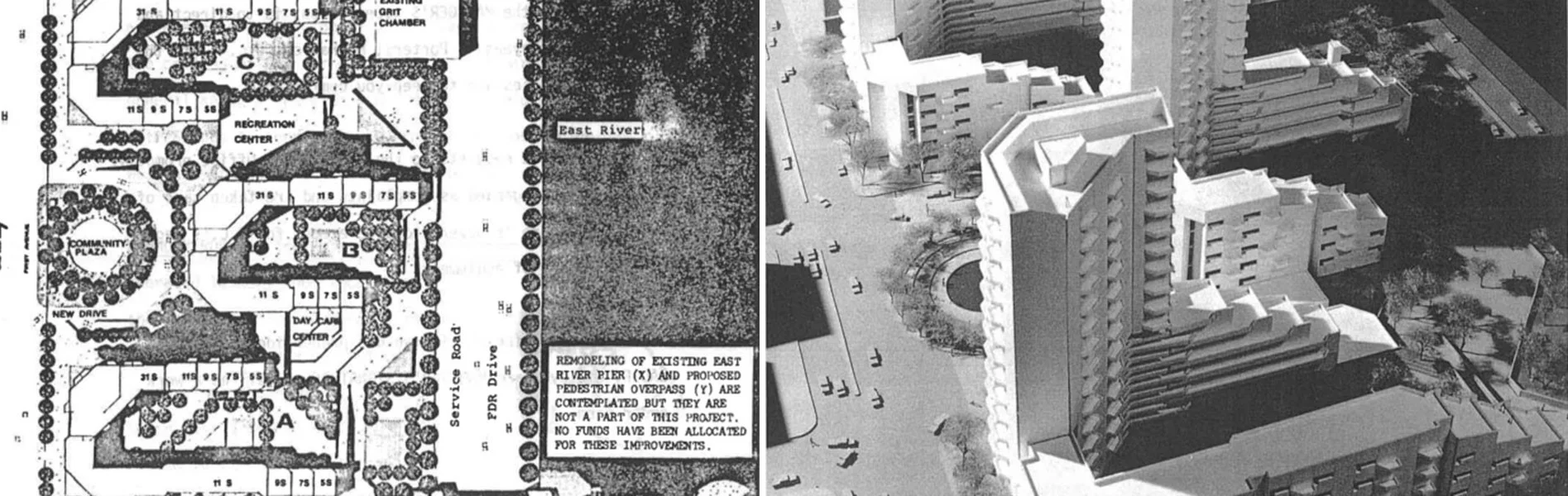

1199 Plaza redesign layout and model. Credit: 1199 Housing Corporation.

By the time construction started twelve years later the plan had been completely redesigned as 1199 Plaza, named after the project's sponsor, Local 1199 Drug and Hospital Workers' Union. The four towers remained, but the low-rise buildings were gone. Instead attached to the four towers was a stepped base leading down to the river, each with its own enclosed courtyard. The massive brown brick towers each form a U-shape facing the river with their rectangular cantilevered balconies extending out from the facade. A Mitchell-Lama co-op development for middle-income residents houses 1600 families in the four 31-story towers. Although the street grid no longer extended through the site as originally planned, the four towers were positioned so the cross streets' line of vision towards the river could extend through the development, even though all traffic is restricted except for 110th Street. Retail space was included in only two of the towers which have frontage directly on First Avenue, with the other two set back from the avenue, one of which allowing room for a landscaped public plaza and traffic circle with the other providing space for a parking lot.

Credit: 1199 Housing Corporation.

While the final product differed vastly from the original proposal and Jane Jacobs' influence, the AIA Guide to New York City states that the bureaucratic red tape that led to the redesign "resulted in one of the city's most impressive and most livable works of multifamiliy housing." (AIA Guide to New York City, 4th edition, p.516)

While the buildings may lack elegance, together and apart they form a fitting formal metaphor for the forces that made them possible. Strong geometric expression and forceful massing reflect strength and ambitions of collaborations between organized labor, state and city agencies. The most interesting aspect of the building's design are the arms that step down from towers and wrap around elevated plazas as they descend towards the river. There are many things to unpack when analyzing the design: The present and powerful frontage to First Avenue – while the buildings neither meet the sidewalk or directly relate to the surrounding low-rise buildings or public housing projects – offers a more explicitly urban siting that operates in response to both proceeding forms of housing, mediating the scales of the two typologies into an alternative form that embraces multiple scales of urbanism while maintaining its own autonomy. The towers hug and protect the elevated courtyards, separating them from the surrounding streets; a benevolent intention at the time, which now proves to actually be detrimental and unsafe when removing "eyes from the street" as Jane Jacobs warned against. The paternalism of Mitchell Lama and organized labor is seen through this protective form, with the alignment of the streets hinting that these buildings are part of the city and the residents are part of the surrounding community, but the unions, city, and state are there to provide support. The play of scale from large towers to low-rise stepped portions and down to seating areas of plazas further articulates and embodies the levels of involvement in the project, from state, unions, and city, down to the local community and residents of the four buildings – together they form a strong formal and urban metaphor for the benevolent, maternal/paternal operation of creating housing and communities at different scales within the city that offer both autonomy and solidarity. It is a powerful architectural representation of the possibilities of a social-democratic urban alternative in which power is shared by government, organized labor, communities of different scales, and individual citizens, all working together in solidarity while maintaining individual autonomy.