EAST SIDE ACCESS (Grand Central Madison)

One of the largest infrastructure projects in the United States is underway beneath the streets of Midtown Manhattan. A new eight-track train terminal is being carved out of the bedrock 150 feet below Grand Central and will soon accommodate 162,000 Long Island Rail Road commuters daily.

East Side Access is a megaproject that connects the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) to Grand Central Terminal, giving commuters from Long Island the option to travel directly to East Midtown, reducing congestion at the overcrowded Penn Station. The project is the first expansion of the LIRR in over a century and it is expected that over half of Penn Station’s peak traffic will be diverted to the new 8-track terminal under Grand Central once opened.

A CENTURY IN THE MAKING

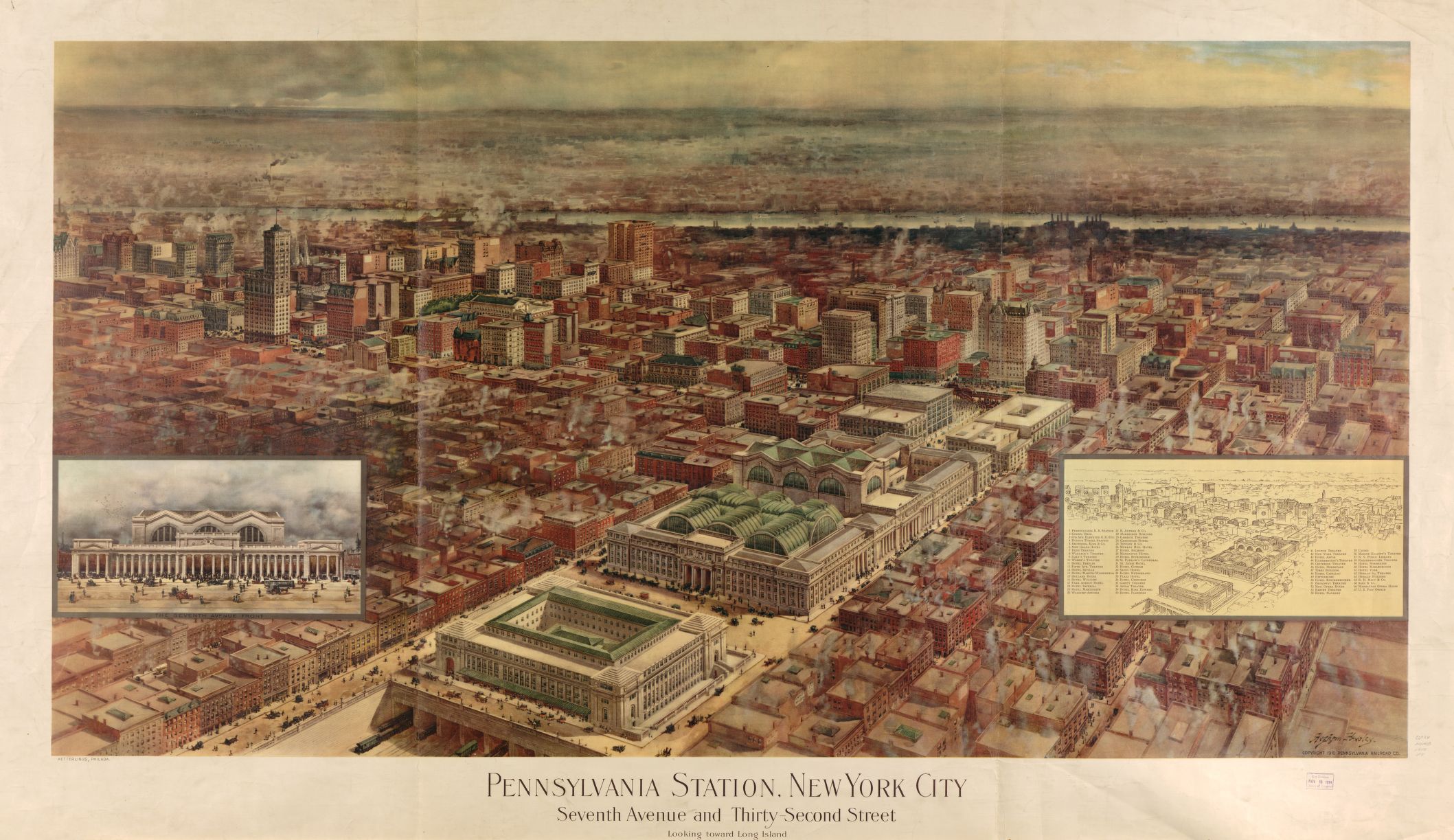

1919 Bird’s-eye and map of Penn Station. Purchase a fine-art print from our web store.

In the 19th Century, LIRR trains bound for Manhattan terminated in Long Island City, Queens, where passengers would board ferries across the East River to 34th Street in Manhattan. LIRR service first came to Manhattan in 1910 when the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), who owned the LIRR, opened Pennsylvania Station on Seventh Avenue between 31st and 33rd Streets. The station was built on the west side of Manhattan to serve as a hub for trains traveling into Manhattan from New Jersey via the newly constructed Hudson River tubes that linked to the PRR network. To the east, the New York Central Railroad (NYCRR), which had operated two previous railroad facilities at 42nd St. and Park Avenue, opened their new Beaux-Arts Grand Central Terminal in 1913. Grand Central would have been a better location for Long Island commuters due to its location on the east side of Manhattan, where more jobs were located, but competition between PRR and NYCRR eliminated any opportunity for direct access for LIRR commuters to the east side of Manhattan over the next several decades.

In the postwar decades, a number of factors including automobile-centered planning and over-regulation of the railroad industry led to the decline of many of the great railroads around the country. During this time, PRR stopped subsidizing the unprofitable Long Island branch, which was then purchased by New York State under the control of the newly established Metropolitan Commuter Transportation Authority (today’s MTA) in 1965. The LIRR was fortunate to separate from PRR, as just three years later, rival railroads PRR and NYCRR declared bankruptcy and merged in 1968 to form Penn Central, which would also fail less than three years later.

TUNNEL TO NOWHERE

Metropolitan Commuter Transportation Authority, 1968.

In 1969, the MTA’s ambitious transit expansion program included an LIRR East Midtown connection, via a new East River tunnel at 63rd Street connecting to a terminal on Third Ave and 48th Street with an office tower on top. The proposal called for a double-decked tunnel; a four-track immersed tube under the East River and Roosevelt Island. The tunnel’s top level would be used by the IND 63rd Street subway line (today’s F and Q) and the bottom for the new LIRR East Midtown connection. With funding secured, construction on began in October 1969.

While construction on the tunnel progressed, the MTA continued planning the Third Avenue LIRR terminal, dubbed the Metropolitan Transportation Center, which they estimated would cost $341 million. The ‘69 expansion plan also included a proposal for constructing the Second Avenue Subway, which would have provided subway connections to the LIRR terminal. This made the Third Avenue location ideal due to its numerous connections for LIRR passengers to Lexington, Flushing and Second Avenue subway lines, Grand Central Terminal, bus lines, taxis, and parking.

Rendering of Metropolitan Transit Center for LIRR on Third Avenue. Metropolitan Commuter Transportation Authority, 1968.

Planning map showing the convergence of LIRR lines in Queens and the proposed Metropolitan Transportation Center on Thirds Avenue and 48th Street. Metropolitan Commuter Transportation Authority, 1968.

Residents of the Turtle Bay neighborhood opposed the new transportation center, forcing the MTA to study alternatives, including moving it to Grand Central. But the federal government, who partially funded the project, directed New York State to first expand and modernize Grand Central – which had just been saved from demolition and designated a historic landmark, before construction of the Third Avenue Terminal could proceed. A 1975 MTA report on the Grand Central alternative proposed dedicating 20 lower-level tracks for LIRR service; ten tracks on the west side and ten storage tracks on the east side, moving some Metro-North lines to the upper level. Two years later the MTA voted to approve the Grand Central site, but the emerging fiscal crisis nearly resulted in the entire transit expansion program being sidelined. Economic problems also delayed the construction of the 63rd Street tunnel, which took over two decades to complete. By 1980, it was reported that the lower level tracks in the tunnel would never see a LIRR train. The New York Times referred to this as a “dead-end to nowhere.”

In 1989, twenty-one years after construction started, the 63rd Street tunnel opened with F train subway service and a new station on Roosevelt Island. With two vacant tracks below, terminating at 29th Street in Long Island City and 63rd Street and Second Avenue in Manhattan, the lower level would lay dormant for three decades.

PLANS REVIVED

In 1996, plans for the LIRR extension to Midtown were revived with a report recommending using Grand Central’s upper-level Metro-North tracks and loop track for LIRR service. After assessing the technical viability, it was concluded that the proposal would interfere with Metro-North service, overload the current customer capacity at Grand Central, and eliminate any opportunity for future Metro-North expansion. Despite not having a viable alternative, New York senator Alfonse M. D'Amato sought federal funding for the project, which was estimated to cost a total of $2.1 billion when it opened in 2010.

In addition to studying the Grand Central alternative, planners evaluated a number of other options for Long Island commuters including express bus service, HOV lanes, and various East Side LIRR terminals. An Environmental Review in 1999 concluded the LIRR had become the busiest commuter railway in the country, and their East River tunnels, signals, interlocking systems, and Penn Station concourse were all operating over capacity. Furthermore, ridership was projected to keep growing, along with white-collar job growth in Manhattan, particularly East Midtown. After exploring a number of possibilities the report suggested a preferred alternative:

“LIRR service directly into GCT via the existing 63rd Street Tunnel under the East River and new tunnels deep under Manhattan streets... [will] alleviate congestion on the region’s highways and many NYCT subway lines, reduce travel time from Long Island into East Midtown, provide a new station serving Long Island City and Sunnyside, improve air quality in the region, and help improve the region’s overall socioeconomic condition in the future.”

Map showing alternative using Grand Central’s upper-level Metro-North tracks and loop track for LIRR. This option was ultimately not selected due to its disruption to Metro North service. East Side Access Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS)

The plan would utilize the 63rd Street “dead end to nowhere” tunnel, linking it with new tunnels that would be bored under Park Avenue. Finally, a new concourse would be constructed to the west of the lower level of Grand Central, connecting four new platforms in two 1,100-foot-long train terminals bored out of bedrock deep below. This was seen as the most favorable alternative because it reduced the impact on the current tunnels and buildings along Park Avenue, and did not interfere with Metro-North service.

The report’s other findings further emphasized the need for East Side Access. By 2020, 110,000 riders would travel to Penn Station in the morning rush hour, an increase of 25,000 from 1995. With East Side Access, more than half of those riders would choose to go to Grand Central Terminal. The benefits included alleviating overcrowding on subway lines, as 8,000 fewer people would ride the subways from Queens into Manhattan during peak times.

To politicians, East Side Access seemed fairly straight forward – the tunnel connecting Manhattan and Queens had already been built, now it just needed to be connected to Grand Central and LIRR lines in Queens. Following the report, the MTA proposed a $17 billion budget, which included $1.6 of the estimated $4.3 billion East Side Access project and $700 million for the Second Avenue subway. In 2002 the final plans were approved and construction began.

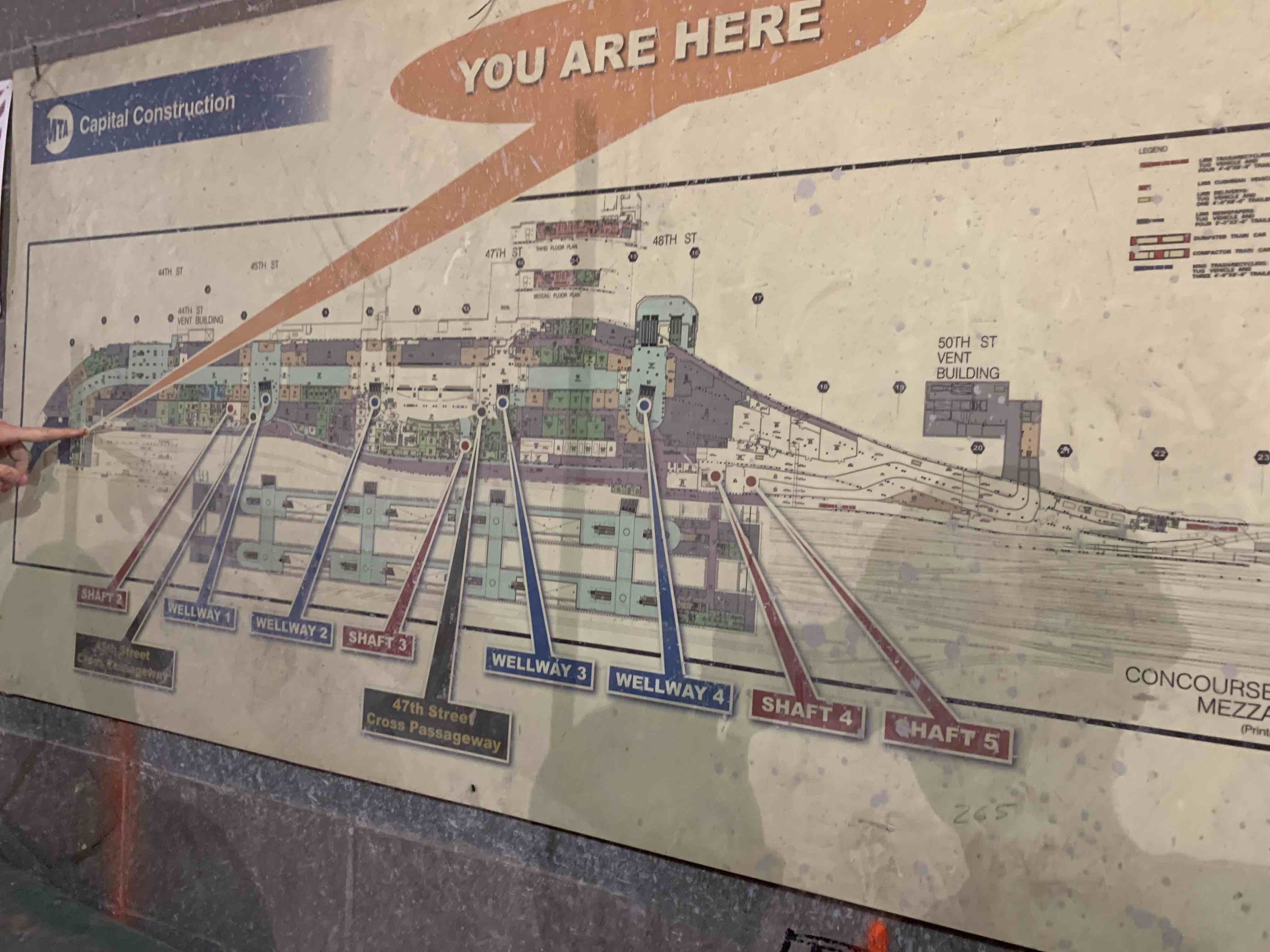

The new terminal under Grand Central will consist of two large caverns, each with three levels containing a total of eight tracks split among four platforms. Additional tunnels continuing south from 42nd Street and ultimately terminating at 38th Street will provide room for train storage. The middle-level mezzanine in each cavern terminal connects to a passenger concourse above that runs below Vanderbilt Avenue via 180 foot long escalators (the longest in the state) and multiple elevator banks. The 350,000 square foot passenger concourse runs from 42nd to 48th Streets and will offer 25,000 square feet of retail space with connections to Grand Central’s main concourse and off-street connections along Madison Avenue.

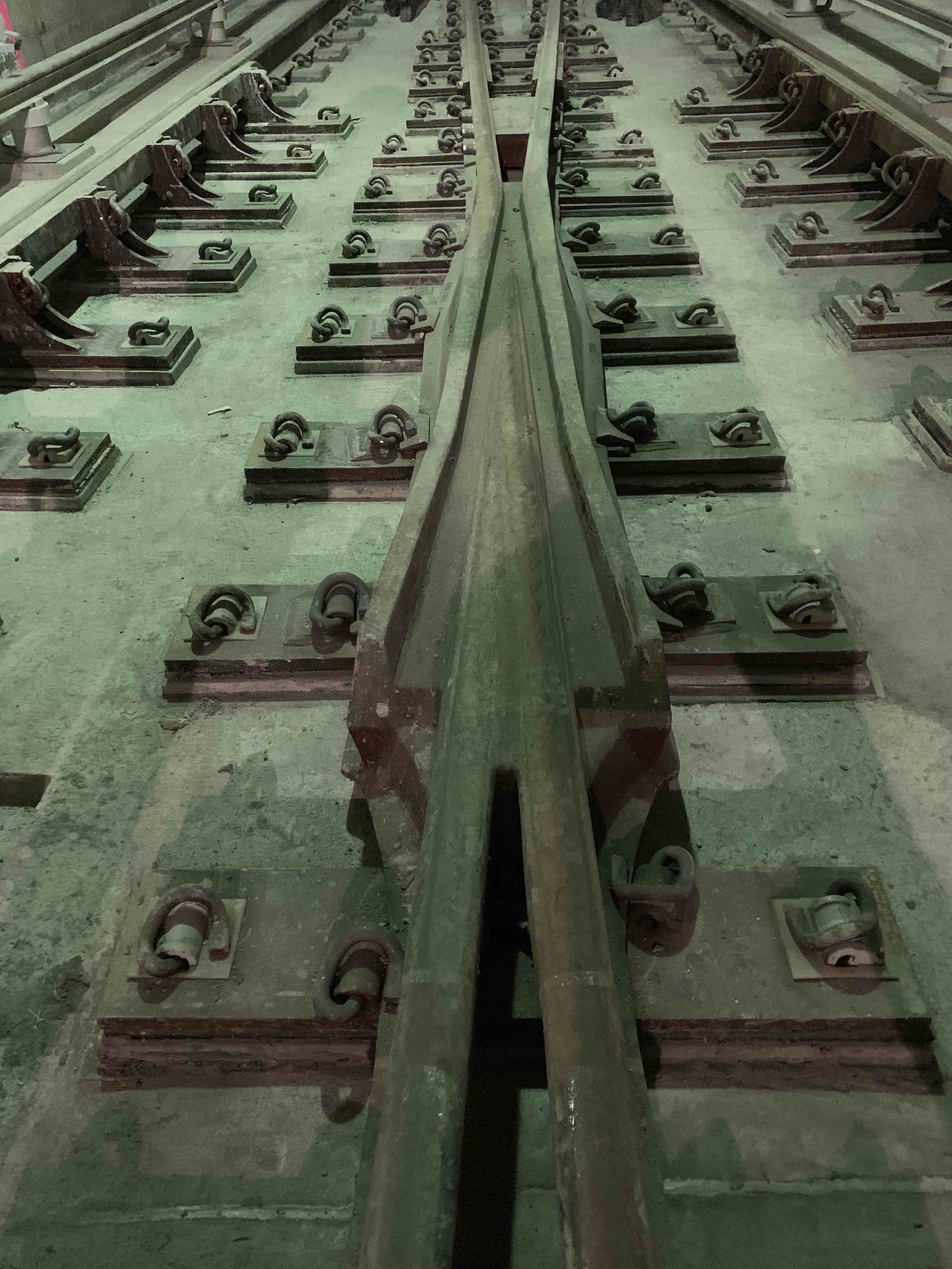

In Queens, over $1 billion in improvements have been made at Harold Interlocking, a large rail junction for Amtrak and LIRR, including new tracks, signals, switches, communications, power systems, and tunnels, eventually connecting eleven LIRR branches with Grand Central (see construction photos above).

Top: Cavern and Concourse 3D View. Above: Profile showing the concourse and platforms, looking west. Right: Section view looking north showing the concourse under Park Ave and the two cavers of platforms under Metro North tracks. Credit: MTA Capital Construction.

MOST EXPENSIVE MILE OF TUNNEL IN THE WORLD

East Side Access proved to be much more complicated and expensive than originally anticipated. Still, it is an enormous undertaking, and what has been accomplished is remarkable. After transporting two 640-ton hard rock tunnel-boring machines in pieces through a Queens access point, they were assembled under 63rd Street and Second Avenue. The MTA blasted and bored eight miles of new tunnels leaving one of these machines buried underground forever.

Construction below Grand Central Terminal, May 21, 2014. Credit: MTA Capital Construction / Rehema Trimiew.

150 feet below Grand Central Terminal, workers labored 24 hours a day, carving a new station out of bedrock under one of the densest and busiest areas of the city without disrupting trains or pedestrians above. Most people who pass through Grand Central daily or work in adjacent buildings have no idea construction has been going on below them for over a decade. On East 50th Street a new park was built above a ventilation facility to mitigate noise pollution with sound absorbing planters and a color-changing waterfall. In the 63rd Street tunnel, they built a conveyor belt system to transport all the bored material from Manhattan through the opening in Queens.

50th Street Commons, a 2,400-square-foot urban space, located at 48 East 50th Street above an East Side Access ventilation facility. Credit: MTA Captial Construction.

Still, costs have ballooned, taking away resources from other transit projects and raising questions about the MTA’s ability to control budgets and cut down on wasteful spending. The most recent estimate is projected to reach $11.1 billion once completed – more than 2.5 times the original budget. The New York Times labeled East Side Access the most expensive mile of track on earth, reporting it cost $3.5 billion for each mile, seven times the worldwide average and even higher than the $2.5 billion per mile of the Second Avenue Subway. The diminished credibility of the MTA following these over-budget, over-schedule projects will make it more challenging to attempt much-needed large-scale transit improvements in the future. Unlike the early privately controlled railroads, all of the funding has come from taxpayers, with the state accounting for 75% of the budget and the federal government making up the remainder.

Cross-section view looking west, showing the LIRR concourse and tracks’ proximity to Metro North, streets and buildings above. Credit: MTA Capital Construction.

There are many factors that account for the exorbitant price tag: According to reporting by The New York Times and City Journal, large projects were split up into multiple contracts that were not competitively bid on, due to lack of competition, and difficult to coordinate. The MTA spent $4.4 billion (43% of the total expense) on labor, with unions requiring job sites be staffed with four times the number of workers compared to similar projects around the world. The New York Times reported in 2017 that 900 workers were getting paid for tunneling that only required 700 jobs. After finding out about the 200 additional workers, Michael Horodniceanu, then the head of construction of the MTA, confirmed "nobody knew what those people were doing, if they were doing anything [or how long they'd been employed]...All we knew is they were each being paid about $1,000 every day.” Many critics have labeled the decision to build directly under Grand Central a “fatal flaw,” but the disruption to peak Metro-North service for several years in addition to removing any chance for future growth that would have resulted from the alternative cannot be quantified.

In Queens, a second major stressor has been Amtrak’s control of Harold Interlocking and their unwillingness to streamline construction efforts with the MTA. The two agencies have had a dysfunctional history, and Amtrak has delayed the construction schedule, which has caused cost overruns. For example, Amtrak required they assist all MTA construction at Harold with “force protection,” then couldn’t find enough workers to do the job. Additionally, Amtrak struggled to provide assistance on weekends, the opportune time for the MTA to get work done when there are fewer trains.

Despite the delays and final price tag, East Side Access finally looks like a real train terminal, and it is spectacular. When it opens in December 2022 it expected to serve 162,000 daily riders, shaving off forty minutes in commuting time and taking stress off regional transit including Penn Station and the East River tunnels that are in dire need of repair after being severely damaged in Hurricane Sandy.

The new terminal is a worthy addition to Grand Central – it was smartly designed to emulate and compliment Grand Central’s Beaux-Arts aesthetic, using the same marble from quarries in Italy and Turkey Cornelius Vanderbilt selected over a century ago.

East Side Access will be a major improvement for LIRR commuters who have entered New York City for the past half-century through the low-ceilinged, dark, drab and crowded Penn Station, frequently labeled “the most hated train station in America.” As historian Vincent Scully famously remarked, "one entered the city like a god; one scuttles in now like a rat." East Side Access is an opportunity to correct this past – the demolition of the original Beaux-Arts Pennsylvania Station, demolished in 1966 – by providing a new modern space for commuters. Grand Central Terminal is loved by New Yorkers because it makes them feel great when they enter it. New York City has to continue to invest in public transit infrastructure projects and in doing so, create monumental spaces like the great train stations we built a century ago. When it opens in three years, East Side Access will be a shining example of the next era of New York City’s great mass transit projects.

View our photos showing the status of the construction site from November 29, 2018 below. Special thanks to the team at MTACC East Side Access.

Sources:

Metropolitan Transportation, a Program for Action. Report to Nelson A. Rockefeller, Governor of New York. Metropolitan Commuter Transportation Authority, 1968.

East Side Access Project Alternatives. MTA Capital Construction.

East Side Access Environmental Impact Statement. MTA Capital Construction.

East Side Access Record of Decision. MTA Capital Construction.

Deep Below Park Avenue, a Monster at Rest. The New York Times.

Tunnel Project, Five Years Old, Won't Be Used. The New York Times.

The Most Expensive Mile of Subway Track on Earth. The New York Times.