One Hundred Barclay

When constructed in 1927, the Barclay-Vesey Building at 140 West Street was one of the first examples of a new form of architecture that would soon define the next quarter-century of high-rise development in New York City and around the world. Shaped by the 1916 zoning law, which required setbacks to allow light and air to reach the street, this new style created by municipal regulation soon became an aesthetic, often accompanied by Art Deco ornamentation.

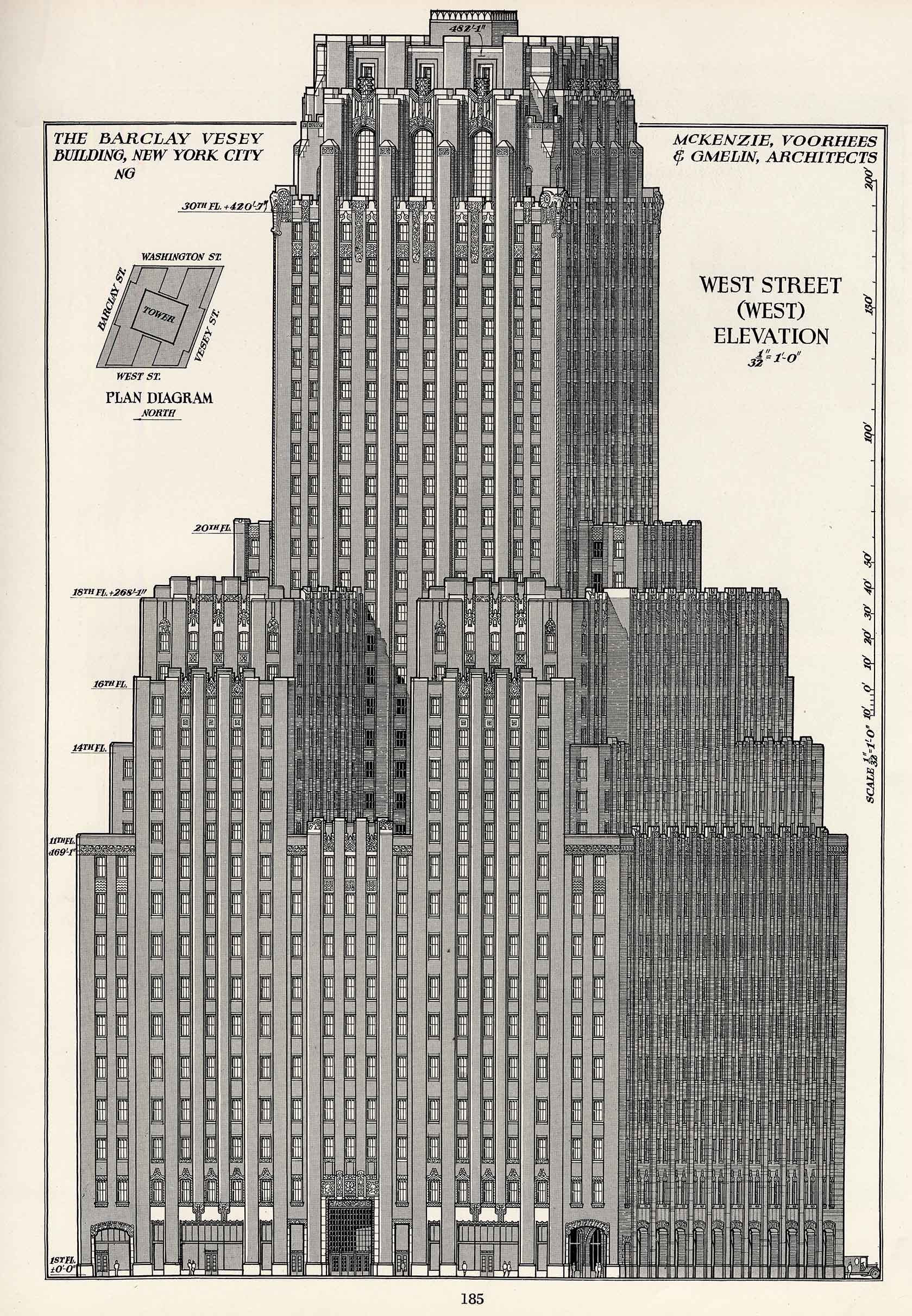

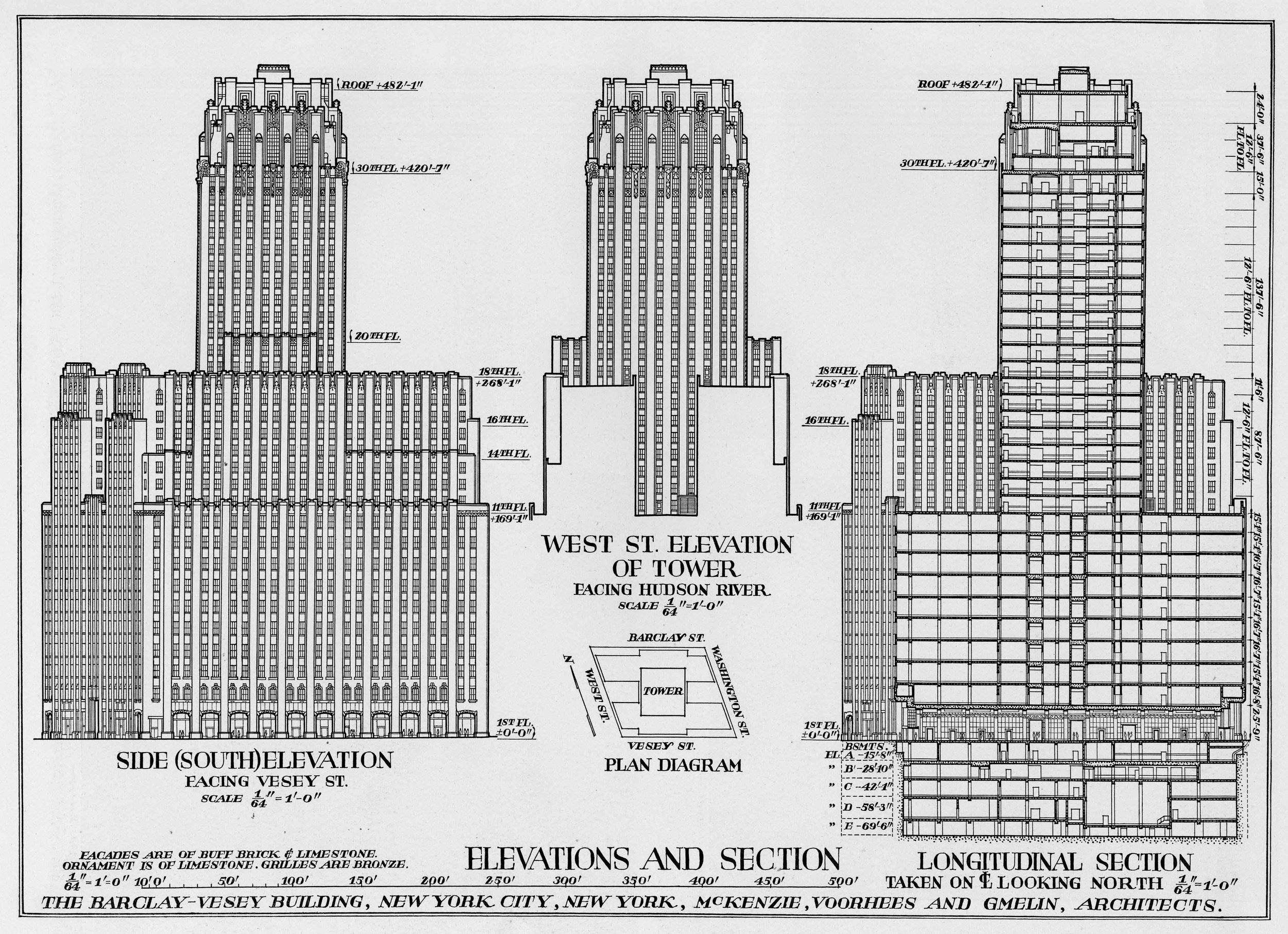

Designed in 1923 by Ralph Walker for the offices of the New York Telephone Company, the skyscraper was referred to the Barclay-Vesey Building due to its proximity between Barclay and Vesey Streets on the Lower West Side of Manhattan. At 498 feet, the skyscraper totaled over 1.2 million square feet of office space with five sub levels of telephone switching centers. When it opened in 1926 the structure was defined by its overwhelming monumentality, which was balanced through its ornamentation and form, giving the building individuality and human scale while also appearing solid and powerful.

The Barclay Vesey Building is one of the earliest examples of the the 1916 Zoning Law that introduced the “setback principle,” requiring buildings over a certain height to follow a setback line, allowing sunlight to reach the street. The regulation, which did not set a height limit but regulated the building's form, stayed in effect for 45 years, shaping some of the city's most iconic buildings such as the Empire State and Chrysler Buildings. The Barclay Vesey was one of the first.

The base of the building, shaped by the irregular block rises straight up from the sidewalk to the tenth floor, where dramatic setbacks reveal a square tower that continues before topping out at 32 floors. The cornice of each setback is adorned with ornament; elephant heads with their trunks dangling down the facade, foliage, and cherubs. As The Skyscraper Museum explains, the bulky base, rising directly up from the lot lines, “was only possible because of the switching machinery it contained; windows were unnecessary, so the entire internal core could be utilized. Ralph Walker used the mandated set-backs to create a well-lit office tower above the switching floors, beautifully matching form to function.”

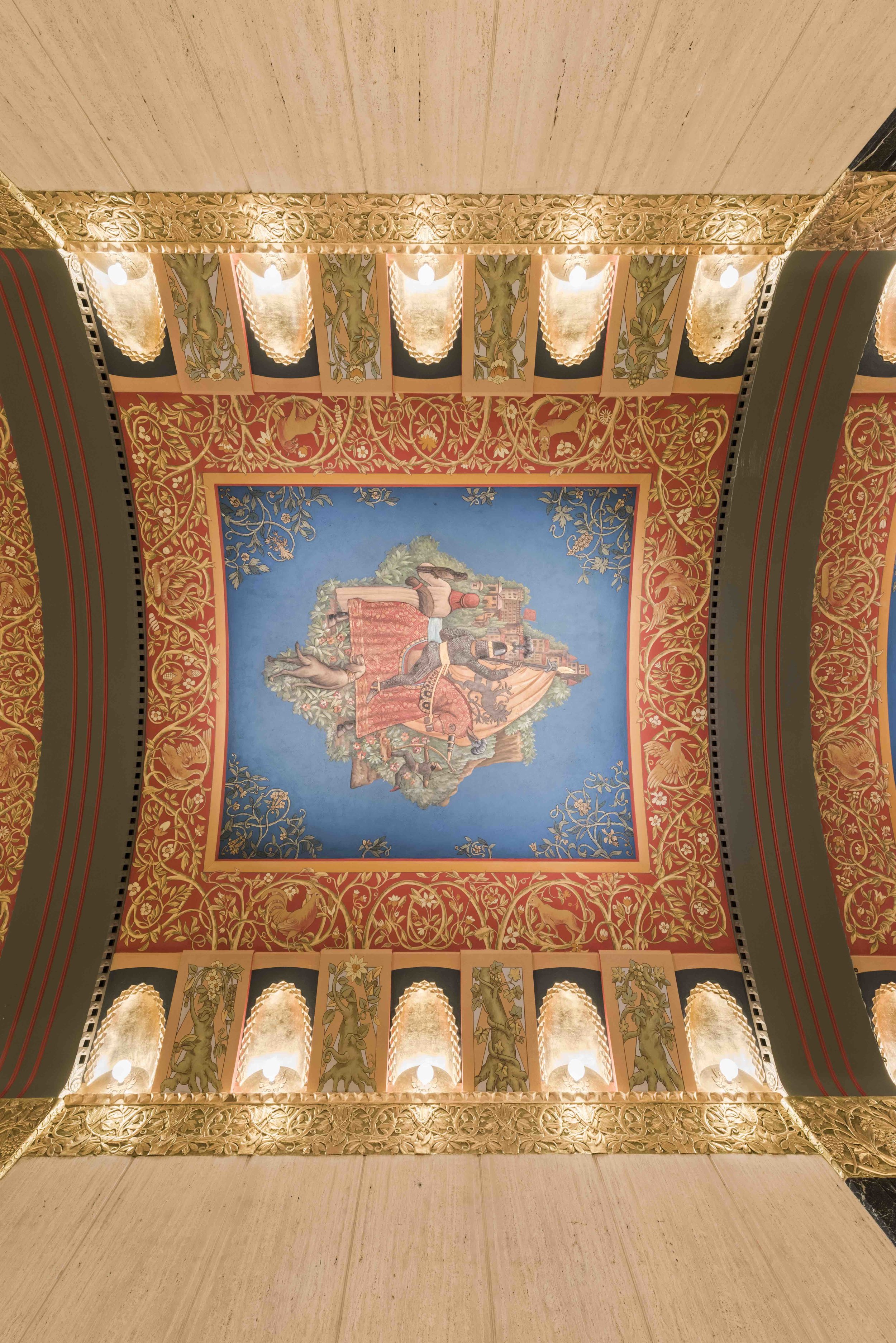

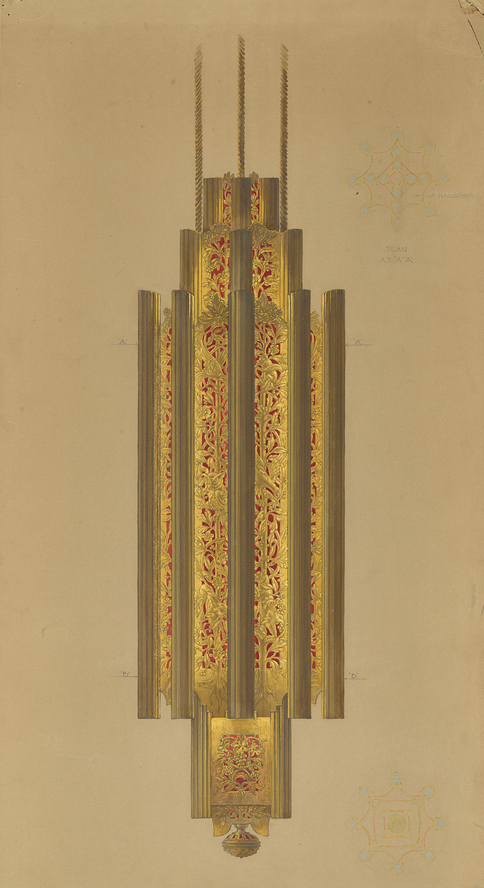

On the building’s south side, a Guastovino-tiled vaulted arcade enclosed Vesey Street, blending public and private space and offering protection and grandeur to passing pedestrians. Inside, a grand lobby forms a corridor the length of the building, with marble walls, travertine floors, and bronze medallions, topped with exquisite murals illustrating advances in communications.

Walker's design was massively influential, pushing other architects to adopt the form in their work. Walker would go on to design other iconic New York City skyscrapers including One Wall Street, the Western Union Building (60 Hudson) and the AT&T Long Lines Building (32 Sixth Ave). In 1957 The New York Times would name Walker "Architect of the Century."

Barclay Vesey Building seen from the Singer Building, 1926.

The skyscraper was in the path of destruction on 9/11, bordering the northern edge of the World Trade Center campus with close proximity to the Twin Towers, and next door to the collapsed 7 World Trade. Luckily, the building's thick masonry exterior helped to shield it from much of the falling debris and absorb the energy from the collapsed towers with no interior fires. Still, the building experienced extensive damage with entire portions of the facade ripped off its steel skeleton. The underground Verizon cable conduits and infrastructure were also flooded and heavily damaged. In 2002, the New York Times detailed the damages to the building: “It took hits on two sides. First, the steel hurled from the collapsing towers smashed into the building's south face, penetrating an underground vault containing thousands of telephone cables. Later that day, 7 World Trade Center, a 47-story skyscraper just to the east, came tumbling down, its ruins slumping like a slain giant against the Verizon Building's east facade.The remains of the collapsed trade center buildings have been picked away, but the wounds they created are still visible. Two-foot-wide steel support columns at the east facade of the Verizon Building are bent inward like crumpled car fenders. A hole in this face of the building reaches as high as eight stories from the ground, and is covered by nothing more than white sheeting.”

The Times noted the repair bill would cost “three-quarters of the Chrysler Building's estimated total value.”

Restoration following 9/11 was done by Tishman Construction and cost a total of $1.4 billion, a large portion of which went to carefully restoring the interior ornament, at times required injecting acrylic resin into the lobby murals to restore and paint and plaster. Facade ornament was also restored, with new motif designs carved into limestone sourced from Indiana.

In 2013 Verizon – New York Telephone’s successor – sold the top 22 floors to Magnum Real Estate Group, who converted the floors into loft residences under the name 100 Barclay. During the conversion, the lobby was completely restored with a new entrance on the Barclay Street side of the building.

We recently previewed the penthouse and model apartments and were impressed by the restoration and incorporation of Walker's original design paired with a contemporary elegance. The units feature high-end materials, sprawling views of the city, and 40,000 sq. ft. of amenities including a 82-foot lap pool. The skyscraper's dramatic setbacks were utilized as landscaped terraces with 360-degree views of the city. Because the base of the building houses Verizon's internet substation for Downtown, residents have access to FIOS 1 Gigabyte per second internet!

The building's breathtaking penthouse is one of the largest in the city, with over 14,500 square feet across two full floors. One of the most striking features of the space is the 21-foot ceiling heights and 9-by-20-foot original arched windows offering iconic 360-degree vistas of the city skyline, Empire State Building, Statue of Liberty, and Hudson River. Designed by Brad Ford, the interior is half built out, leaving the rest of the space for customization.

For those who may not make it up to see the residences, the breathtaking lobby is an interior landmark, which means it is open to the public. Covered in bronze, marble and travertine, with murals depicting communication through the ages, it is one of the most incredible interiors in the entire city – and in it’s original state. Peek inside to get an idea of how it looked when the Art Deco jewel first opened in 1927!