REVIVING THE TIMES SQUARE THEATER

Following decades of neglect, conversion, and demolition, in the late 80s, Times Square theaters began a revival that ignited the resurgence of the district. Since the Depression, many historic theaters in the area had been converted to run cheap films, adult entertainment, or were demolished. As Disney and Mayor Giuliani pushed for renewal, preservationists fought to take back the surviving theaters, eventually restoring many to their original glory. One of these original opulent theaters that solidified Times Square as the city’s theater district narrowly averted multiple demolition attempts but failed at adaptive reuses for three decades. Today this legendary but forgotten theater is undergoing a dynamic multi-level renovation to be transformed into an iconic retail destination in the heart of one of the world’s most visible and energetic environs.

The Times Square, two years after opening (1922)

Originally known as Longacre Square, the horse carriage district on the outskirts of the city was renamed Times Square in 1904 after The New York Times relocated their headquarters from Lower Manhattan to a small triangular lot at the intersection of Broadway and Seventh Avenue at 42nd Street. With the northward growth of Manhattan, the area soon became the new home of the entertainment district, which was quickly accelerated by the introduction of electricity, lighting up billboards and powering the first subway, the IRT, which went right under Times Square on its route between City Hall and Harlem. Theaters quickly followed the northward journey, moving from Union and Madison Squares to Broadway and the adjacent Times Square blocks. As middle and upper-class crowds converged on the district, restaurants, cafes, and hotels quickly engulfed the surrounding blocks. With the construction of Penn Station and Grand Central in 1910 and 1913, the city’s second central business district, Midtown, was quickly developing with Times Square at the center of the action.

Times Square Theater interior, 1920.

The explosion of theaters during the Roaring Twenties cemented Broadway and Times Square as the city’s theater district, with thirty venues popping up along The Great White Way – the lustrous nickname for the area that had become known for its resplendent glowing signage. One of the earliest theaters, Times Square Theater, developed by the Selwyn Brothers, was completed in 1920 on West 42nd Street and Seventh Avenue. Designed by Eugene De Rosa, who designed many of the prominent theaters in the area including the Belmont, Broadway, Criterion, and Vanderbilt, the Times Square was one of two twin theaters with the Apollo next door, also designed by De Rosa. Although located on 43rd Street, the Apollo’s entrance shared a facade with the Times Square, which connected to the theater via a 100-foot corridor.

Despite standing only two stories, the Times Square had an imposing presence on 42nd Street. From the sidewalk, the theater's neoclassical limestone facade is interrupted by multiple entranceways under a dental molding and cornice. Above this ground floor, large Corinthian columns adorned the facade, topped with rosettes and gargoyle heads of winged beasts. Behind the columns, a stucco sgraffito frieze illustrates romantic motifs. On each end of the building, a window is encased in arched ornament, above which, four large limestone urns line the parapet. Inside, the theater had a seating capacity of 1,200 and featured modern advancements including soundproofing, fire exits that connected to side passageways.

Architecture and Building magazine described the luxurious theater during its inaugural year:

“Empire in style, worked out in silver, green and black. The walls are silver gray. The touches of green are so delicate in tone that they melt imperceptibly into the grays, and the tapestried orchestra seats continue the color harmony, all standing out in contrast to the background of the carpet, which is black and the curtain in folds of black velvet. From the orchestra floor a grand stairway winds up to the mezzanine, off which lies the ladies’ smoking and retiring room with its every convenience for women guests. The men’s smoking and retiring room is in the basement. It is a beautiful Tudor room paneled with oak wainscoting and extremely inviting to the masculine element.”

The Times Square Theater opened in September 1920 with a production of The Mirage, starring Florence Reed and had many successful shows over the decade before going bankrupt during the Great Depression. The Selwyn Theater across the street was the first of the brother's theaters to be converted from live theater to film, with the invention of the 'Teleview’ an early film apparatus that was fixed to the viewer’s seat using an alternate-frame sequencing method of stereoscopic 3D projection. The Selwyn premiered the technology but ended up being the only theater ever to employ it, as films quickly became the new standard.

All three Selwyn theaters would file for bankruptcy during the Depression; in 1933 the Times Square presented its last live performance and the theater was leased to a new management company, who converted it to show low-budget sensationalist and exploitative films known as “grind-house.” Many other Times Square theaters faced the same fate during the Depression, with conversions to movie theaters, night clubs, and music venues. In 1940 the Times Square’s status as a movie theater was solidified with the insertion of a brick wall behind the screen, dividing the stage in half so retail could occupy the eastern frontage of the lot. Despite the decline in programming, the films kept the Times Square Theater’s doors open when other theaters in the neighborhood faced an even worse fate; demolition. In 1946 Brandt – the company that purchased the Times Square and surrounding five properties – sought to demolish the row of buildings to make way for a skyscraper hotel. The plans were never realized and Brandt affirmed their interest in the theater district, quoted in the Times as being "inspired by a conviction that the amusement center of the city was firmly anchored in the Times Square and Forty-second Street neighborhood.” Despite this, the Times noted Brandt had rejected previous offers to return the old theaters to their "legitimate" use.

The theater never recovered its grandeur of the twenties, and despite the city recovering from the Depression and a booming economy in the postwar years, movies quickly became the most popular form of entertainment and many theaters would never revert to live performances. The Times Square survived for the next several decades showing films, while the nearby Belmont and Vanderbilt theaters – designed by the same architect, De Rosa – were demolished. Brandt’s dream for a skyscraper hotel, while not realized at their West 42nd Street properties, was emblematic of planners and developers’ vision for Times Square in the postwar decades.

Multiple public and private large-scale masterplan proposals during this time period reflected the changing landscape of urban planning in and around Times Square. In 1969, the Regional Plan Association published a report proposing multi-level pedestrian connectors along 42nd Street, including "a mechanical aid to pedestrian circulation, such as a moving belt or new type of shuttle train.” The report also looked at closing Broadway at Times Square for pedestrian use, and an office development of skyscrapers “as large as three World Trade Centers” on the west side of Times Square.

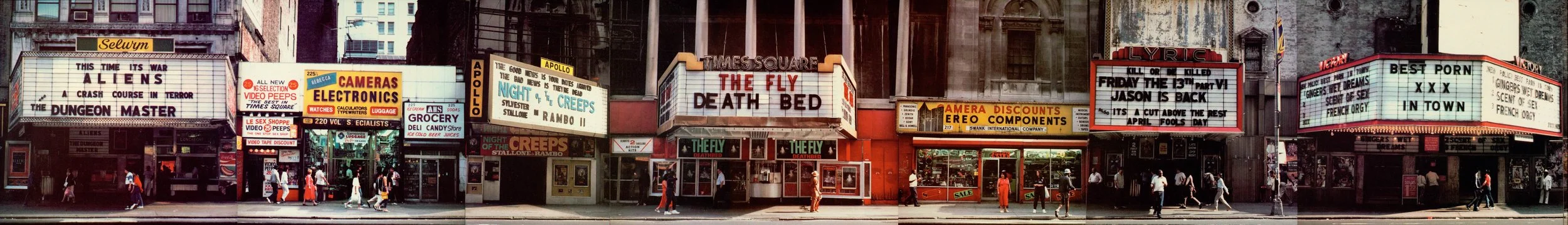

Times Square Theater with the Apollo on the left and retail on the right, 1979.

By the 1970s, the theaters and movie palaces had dramatically deteriorated physically and programmatically, featuring action films, porn, and peep shows. Crime was rampant and unmanageable, causing planners and developers to think of ways to control public spaces and clean up the area. The Marriot Marquis hotel development in the middle of Times Square illustrated this changing urbanism. The development replaced two historic theaters with a modernist hotel tower that was inwardly oriented with a full-height atrium, as the New York Times’s architecture critic Paul Goldberger wrote when the hotel opened, “The Marriott seems to exist for people who would never think of walking the sidewalks of Manhattan.”

The demolition of the theaters that preceded the Marriott hotel – the Morosco and Helen Hayes in 1982 – was a shock for preservationists and theater advocates, igniting protests and eventually leading to the landmarking of twenty-eight theaters in 1988. The Times Square was considered for landmarking and a public hearing was held, but the theater was never designated, likely because it was not operating as a “legitimate” theater. In 1989 the theater closed and a year later it was included in a 99-year sublease along with six other 42nd Street theaters under the newly established organization, The New 42nd Street, an independent, non-profit entrusted with the restoration and oversight of the 42nd Street theaters between 7th and 8th Avenues.

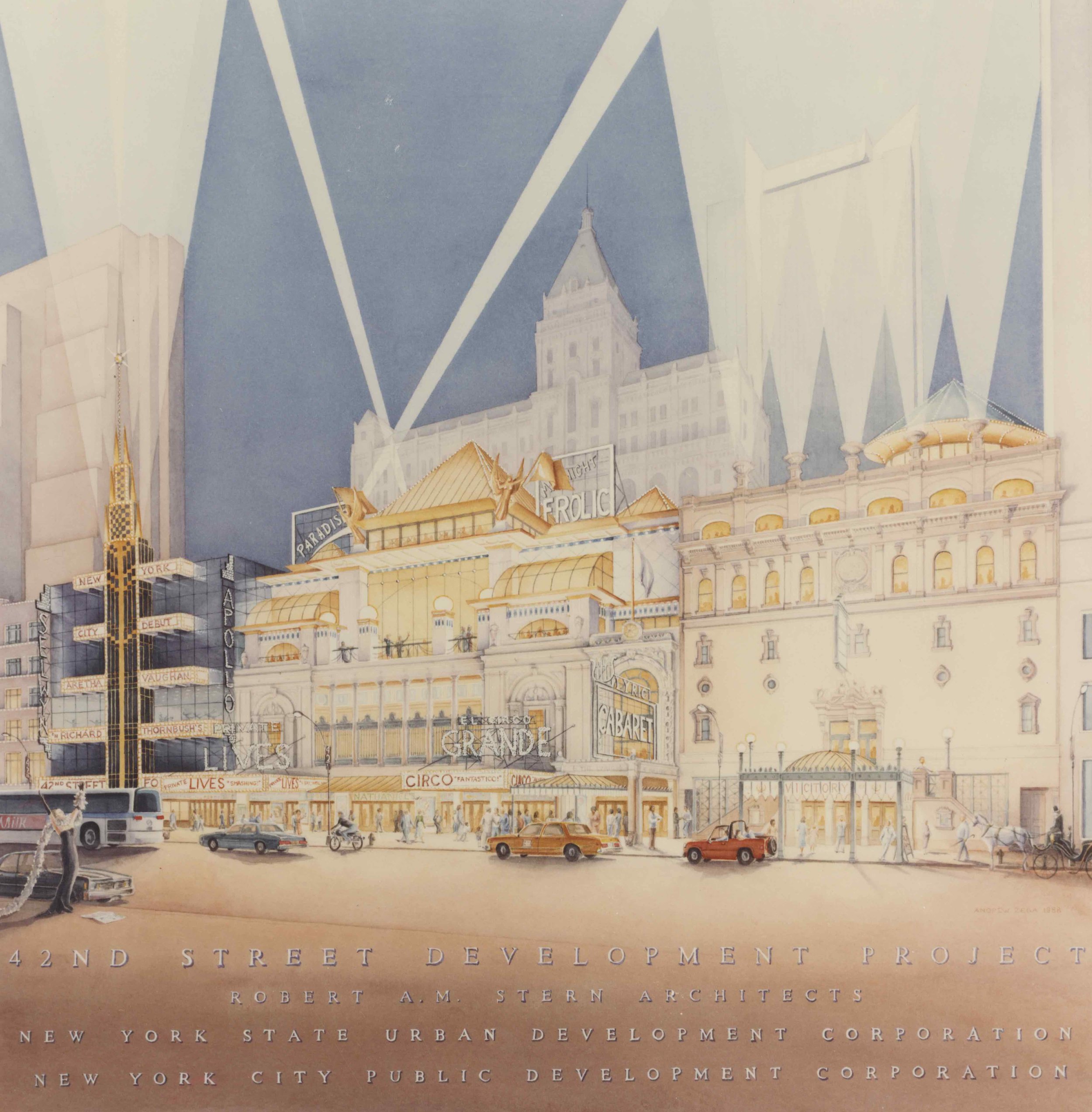

“A City at 42nd Street” proposal, which restored the facade of the Times Square while demolishing the rest for an exhibit atrium.

City at 42nd Street plan, 1978.

One of the earliest large scale development proposals, titled A City at 42nd Street (above), proposed covering 42nd street in order to create a “theme-park like development” that the Times labeled “the biggest discotheque in the city.” Backed by the Ford Foundation and the 42nd Street Redevelopment Corporation, the plan would have required the condemnation of several blocks to make way for “two glass-enclosed atriums, electronic signs, bridges crisscrossing 42d street, and escalators moving through a complex set of spaces making up the display area that will be woven around the old theaters.” (New York Times) The plan was later redesigned for a 500,000 square-foot exhibition and entertainment center, a fifteen-story indoor Ferris wheel, retail shops, restaurants, 4 million square feet of office space and a 2.1 million square feet merchandise mart. As part of the proposal, the Times Square Theater’s facade would be restored, with the rest of the building demolished and repurposed for an exhibit atrium. Despite general public support, Mayor Koch despised the plan, saying it was too much like Disneyland, putting an end to the proposal which required commitment from the city.

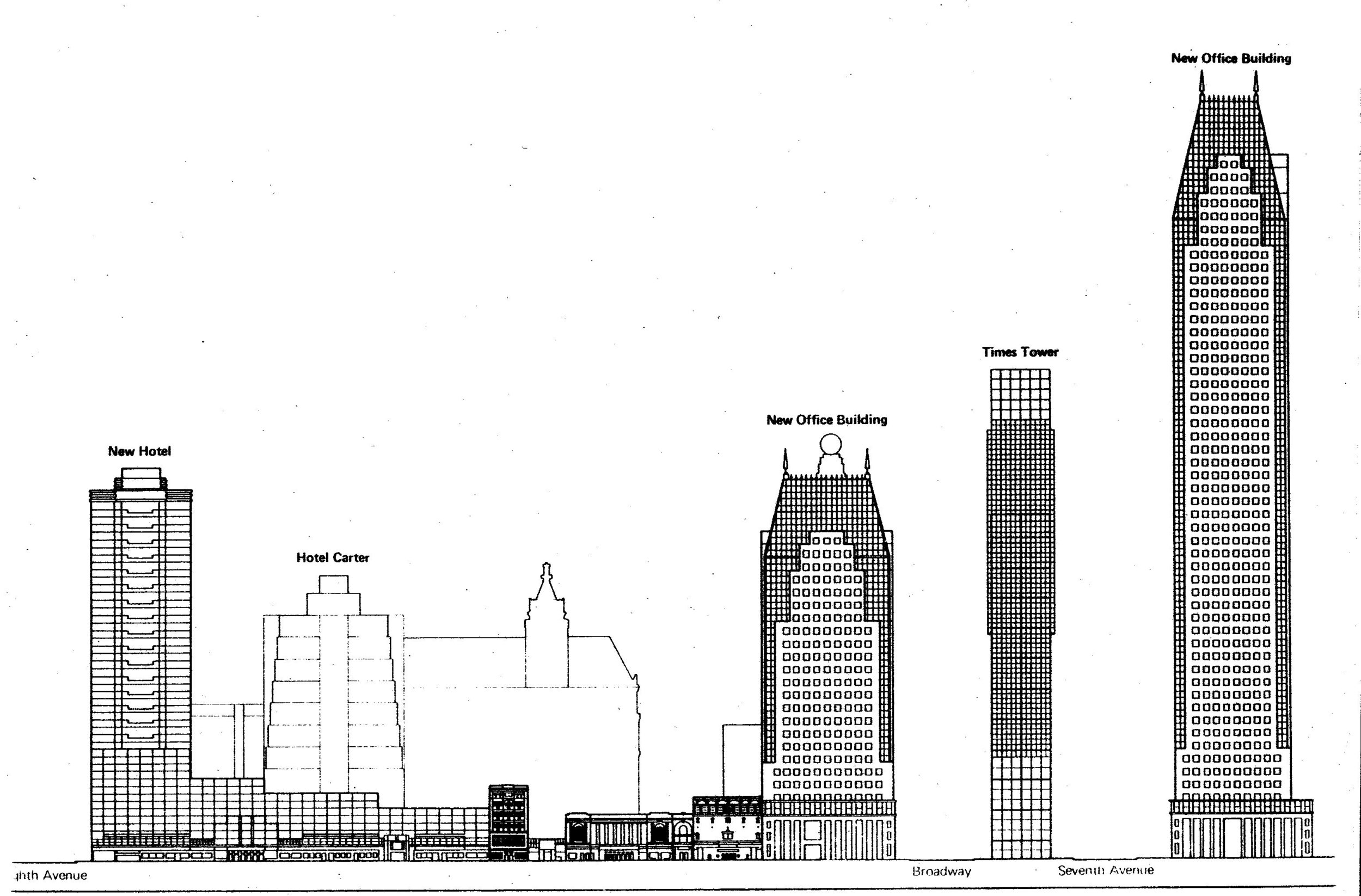

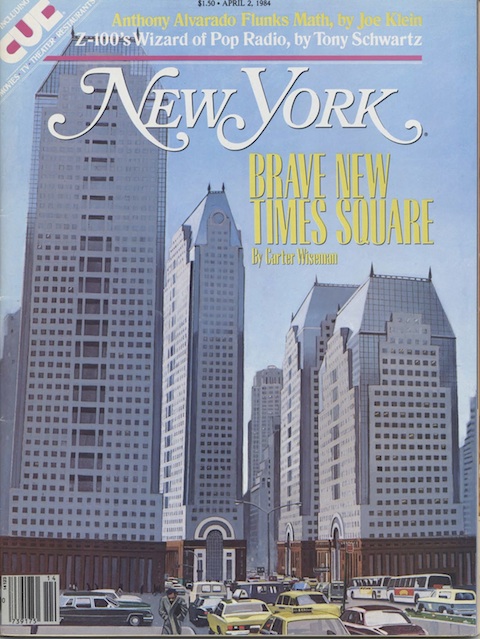

The biggest battle would be over the heart of district – the New York Times’ former headquarters, the Times Tower and surrounding buildings – which faced demolition for a city-backed urban renewal project of postmodern office towers (above). The large office towers would have transformed the area into an office complex and left the Times Square theater in the shadow of a large glass and granite tower. Preservationists and theater groups quickly banded together opposing the development. After a decade-long battle and multiple lawsuits, the postmodern development was abandoned and the Times Square Theater and Times Tower were saved. However, the city still planned to restore the 42nd Street theaters and reduce crime and sex entertainment. In 1992 in order to jump-start the revitalization, the city and state released a plan titled 42nd Street Now!, which recommended a set of guidelines for a retail, entertainment, and hotel complex with vibrant signage, as seen in the rendering below. A year later, Disney signed a deal for the restoration of the largest theater on the block, The New Amsterdam. Disney's presence signaled the tourist-oriented, entertainment and retail revival that was begging to take ahold of Times Square.

While the other theaters on the block were restored in the 1990s, the Times Square underwent various attempted repurposes including a professional wrestling-themed restaurant and store, a comedy club, and a gladiator themed restaurant. All of these proposals fell through, and the theater sat boarded up as the surrounding environment became a major tourist destination, with bright signs, costumed characters, pedestrian plazas and large crowds visiting theaters, stores and restaurants. In 2005 Ecko Unlimited clothing leased the theater with the intention of converting it into a store but soon abandoned plans, then in 2012 a Marvel Comics-themed restaurant met the same fate.

Times Square Theater rendering via Stillman Development International.

In 2017, Stillman Development International, a real estate development and construction firm based in New York City was selected from a pool of over a hundred applicants by The New 42nd Street to restore the theater for adaptive reuse, while preserving and highlighting the theater's historic elements. For the first time, the proposal incorporated the theater’s history and architecture, emphasizing and accentuating its unique characteristics in the future design and use. Stillman proposed a $100 million dollar renovation of the historic facade with a new 52,000 square foot retail space behind, incorporating many of the original architectural details. The developer worked closely with the City's Historic Preservation Committee, who approved the design. One major challenge in repurposing and preserving the space was having to change the use. For almost a century the building had always been used as a theater in some capacity, but modern fire codes, egress requirements, and the limited space make it difficult to restore to its original intent. Modern Broadway productions have expanded their requirements for theaters including front-of-house space and amenities, number of seats and aisles, stage dimensions, dressing rooms, and backstage area, making the Times Square insufficient for modern Broadway shows. The adaptive reuse as a retail location allows the historic elements to be preserved and publicly accessible, cementing the structure's status on 42nd Street for decades to come.

Today, lauded architecture firm Beyer Blinder Belle is leading the project, which involves lifting the original Indiana limestone facade by five feet, giving the structure a more dominating presence on 42nd Street and juxtaposing new modern elements with restored original components from De Rosa's design; like the Corinthian columns, proscenium arch, and ceiling dome. Raising the facade, which will be done using hydraulic lifts, elevates the first floor ceilings to 20 feet, making the space more suitable for retail. Inside the theater, original ornament – like the domed ceiling, arch, stage boxes, and cartouches – have been meticulously cataloged and are being restored off site. The former theater interior will then be converted into a double-height space that connects to a two-floor extension constructed of glass, leading to an outdoor rooftop. The glass will wrap the exterior columns and cantilever over the street, allowing visitors a vista of the street through the columns – and giving pedestrians a view of the original architectural elements for the first time in decades. The relation between the interior space and the public sidewalk is marvelous and emphasizes flow between the two, visibly and physically – proof that planning in Times Square has evolved from the inward-oriented public spaces seen in the Marriott Marquis and similar projects from the 80s.

When complete, the restored structure will offer 52,000 square feet of dynamic multi-level space over five levels for retail, entertainment or restaurant. The restoration will feature the addition of 4,000 square feet of LED billboard signage (currently the Times Square was one of the only frontages on 42nd Street without billboards). Construction started this year and plans to be completed in 2020, in time for the building's 100th anniversary.

42nd Street with the Times Square Theater front and center, 1987. Photo: Battman.