WHITE PLAINS

The Verizon Building, formerly NY Telephone Building in White Plains

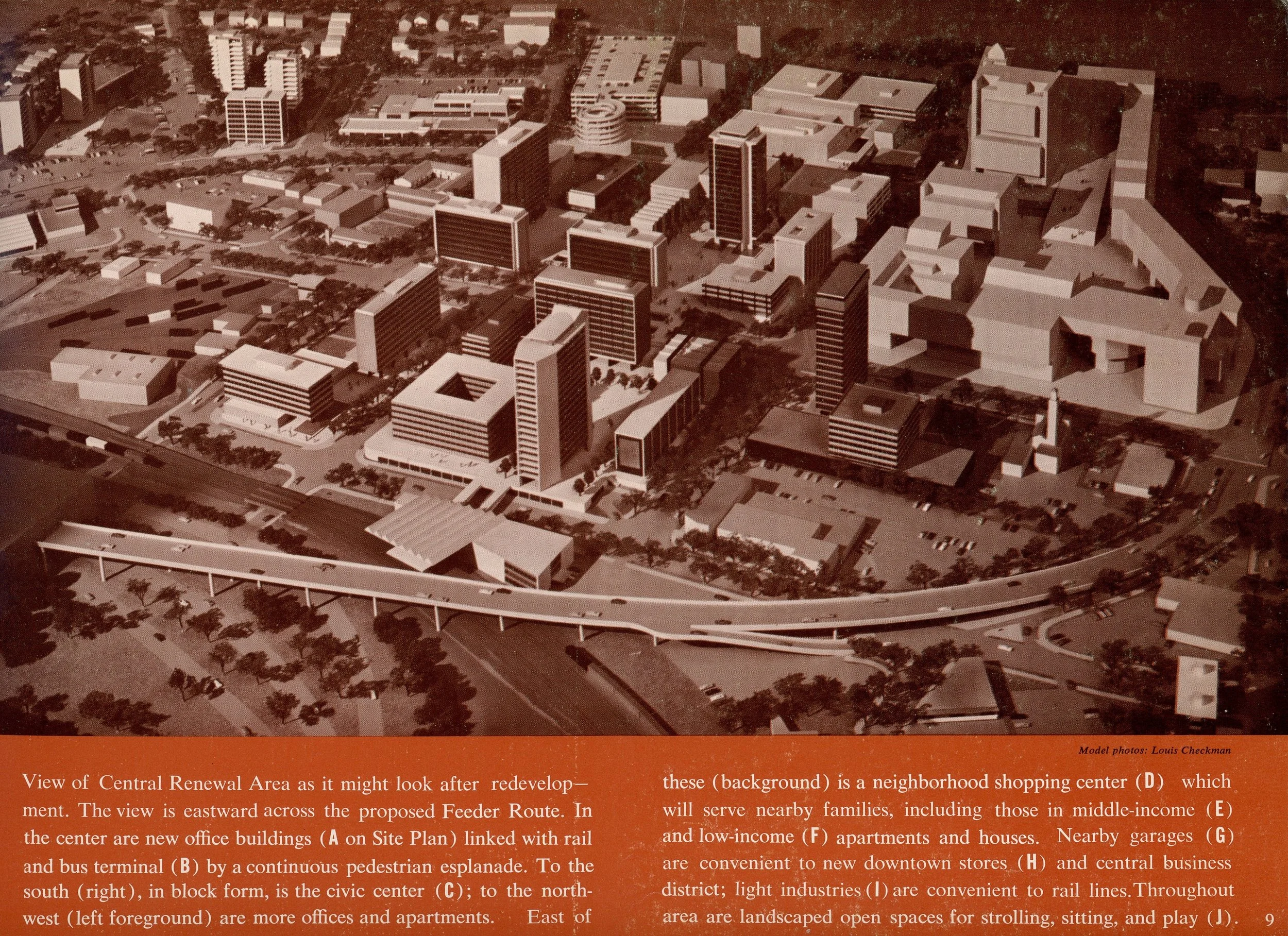

Early model of the White Plains Central Renewal Area. The area shown comprises almost all of downtown White Plains, specifically the areas currently occupied by the Galleria and library. Collection of White Plains Public Library, 1963.

Large-scale urban renewal projects were in no way unique to New York City. White Plains, a suburban city in Westchester County, just north of the Bronx underwent a massive renewal project in its downtown center starting in the late 1960s after a decade of planning. Historically, this area was compromised of a small walkable village with a mix of historic buildings and a stop on the Harlem line just forty minutes from Grand Central Terminal. In the 1950s, a large 20-block swath of the downtown center was slated for redevelopment. The urban renewal area – which would amount to a third of the downtown, essentially the entire central business district – would be rebuilt over the following two decades with high-rise offices, civic buildings, a large shopping mall, mixed-income housing, hotels, and several garages. Parkways, expressways and the New York State Thruway had all either been completed or were under construction during the postwar decades and White Plains would focus much of its revitalization on accommodating automobiles. When the 11-mile Cross-Westchester Expressway opened in 1960, the town built a spur leading downtown, with parking garages and widened streets to accommodate the traffic.

After a decade of planning, in 1966, demolition of the 130-acre site commenced with the displacement of 1251 families, 525 individuals, and 59 businesses. Of the families displaced, 781 remained within the city limits, many occupying new mixed-income housing developments. The $33‐million Westchester County Courthouse (1974), the Westchester One office building (1975), the $5.5 million Galleria at White Plains shopping mall (1978), the $13 million White Plains Library (1973), and the drastically renovated $20 million New York Telephone Building were located at the center of the development. The Galleria Mall, located directly across the street from the Library and Telephone Building occupied four blocks and created a large blank concrete wall from along the sidewalk – as Paul Goldberger described, “a harsh world of concrete.”

“The complex is so big it leaps over an entire city street, and it is so oriented toward the automobile that it is almost impossible to figure out how to enter or leave it as a pedestrian… As a work of architecture, the Galleria does not even rank among the better examples of its own type. On the outside, it looks like a convention center, and on the inside it is garish. If it goes well with anything, it is the forbidding concrete architecture of the new White Plains Library and Westchester County Courthouse across the street, a pair of dreary and bureaucratic imitations of the work of Le Corbusier. Together, all of these buildings make a harsh world of concrete, a world suited more to the landscape of the freeway than to the mood of a city… Within the urban renewal blocks, there is nothing to tie the buildings together, nothing to create a feeling of wholeness to the place - and, more important, nothing to give anyone the impetus to walk. ” (The New York Times, 1983)

Nearly fifteen years after the first buildings were demolished, the village-like character of White Plains was transformed into a modern edge city, more similar to a shopping mall than a town, and almost unidentifiable from its original appearance. Despite the loss of the city's historic character, during this time many major corporations relocated from NYC to suburban locations like White Plains, and at its peak in the 1980s at least fifty Fortune 500 companies had headquarters in Westchester and nearby Fairfield County.

NEW YORK TELEPHONE (VERIZON) BUILDING

Date: 1972

Architect: Haines Lundberg Waehler

Address: 111 Main Street, White Plains NY

Use: Telephone exchange, server center

Verizon Building in 1979 with the Galleria shopping mall construction in the foreground. Collection of White Plains Public Library.

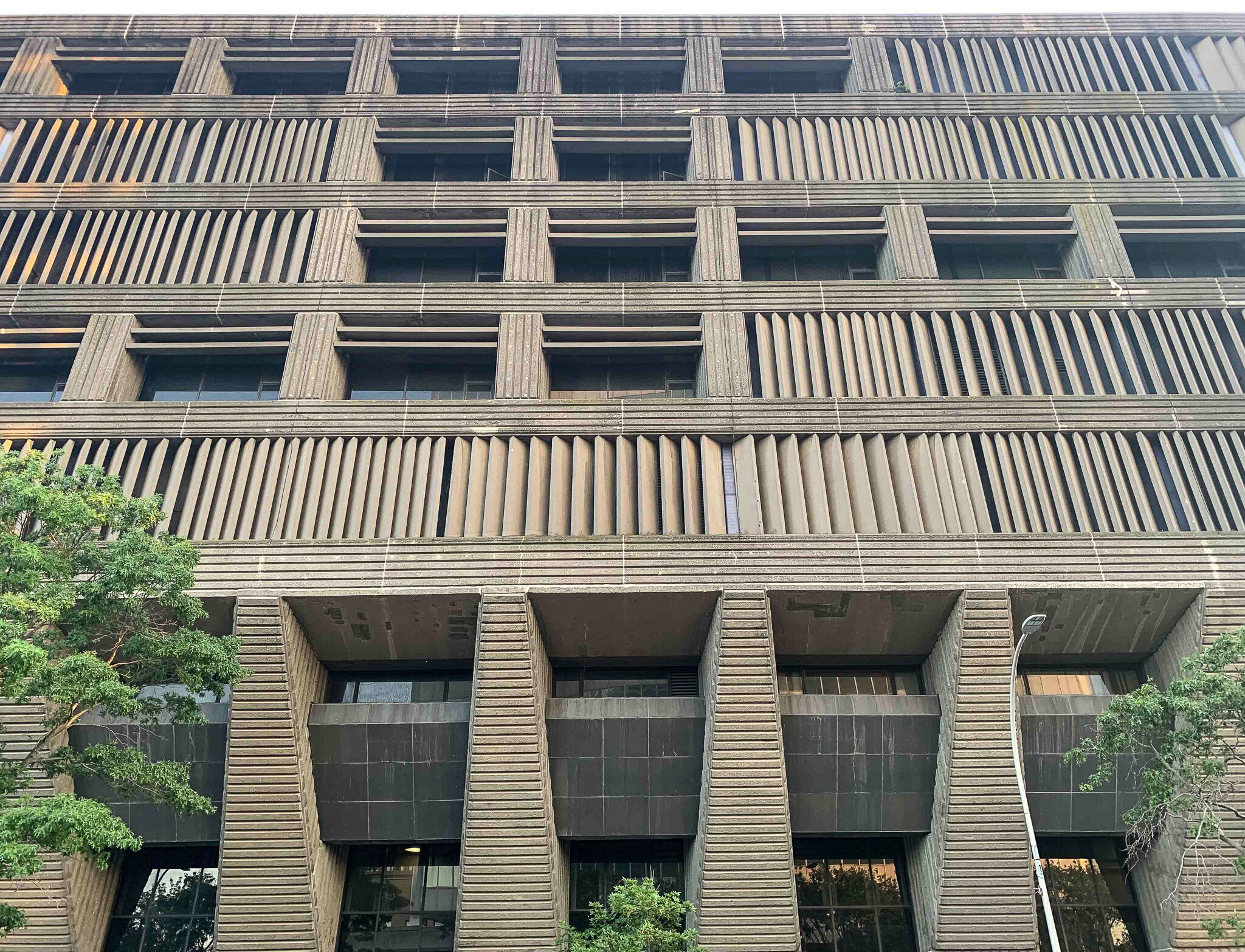

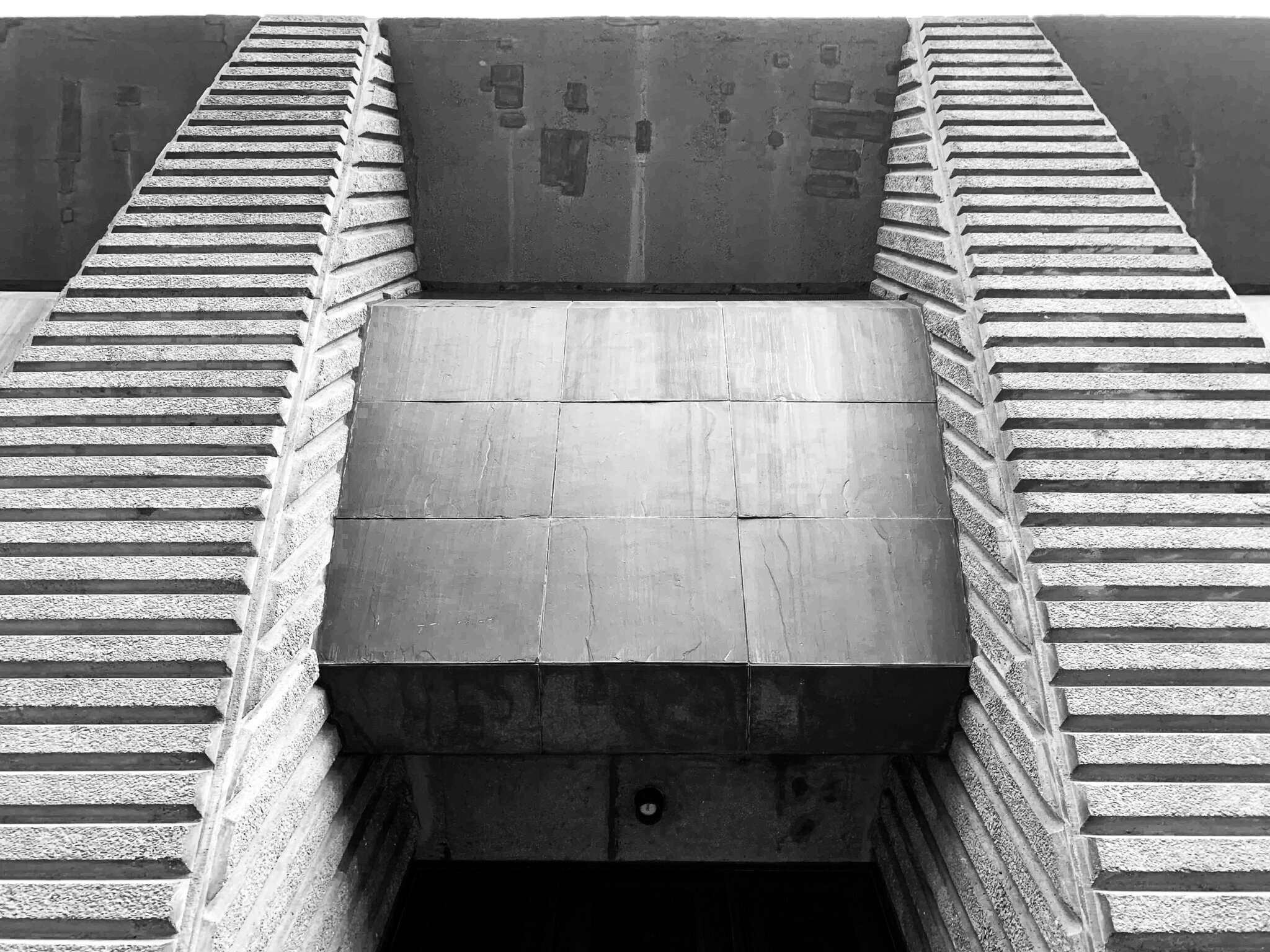

The New York Telephone Company Building was one of the first completed projects in the 130-acre White Plains Urban Renewal Area. A telephone building previously occupied the site, and the company announced plans in 1968 to renovate and expand the structure, citing anticipated growth from the urban renewal area as the “chief reason for the necessary expansion.” (The Reporter Dispatch, 1968, p1). Because of the building’s structural integrity, it was saved from demolition, but the “bulky ugliness” of the building led New York Telephone to an “imaginative design [that] turned this clumsy monster into a modern functional sculpture. In this special instance, the architectural challenge was mainly aesthetic.” (Club Dial, 1974, p.17) The new building added more stories to the present structure, tripling its floor space from 113,00 square-feet to 343,000. A new facade was also added, radically altering it from its original appearance. Working with the Urban Renewal Agency, Spring Street, which previously intersected the site was closed and incorporated into the superblock for use as a public plaza. Telephone companies constructed many of these functional but overbearing structures in cities across the country. Like the Long Lines Building at 33 Thomas Street in Manhattan, the thick, bulky exterior was designed with function over aesthetic. Inside, the building houses switches and equipment, “the most complex and sophisticated electronic equipment now available for rapid and efficient telephone service” as described by company officials. (The Reporter Dispatch, 1968, p15) New York Telephone Company’s architect Haines Lundberg Waehler designed a heavy concrete and granite box of a building. It features two very distinct striated concrete facades, which extend outward from the core at street level before rising straight up. The windows are deep and recessed, sometimes covered by angled concrete louvers. The north and south faces of the building are windowless and sheathed in flat granite panels. The building shares the block with a glass postmodern office building, separated by a public green space in the middle of the block.

The structure's design is especially interesting because of the opposing volumes and characteristics of the facade. The pre-cast facade with hyper-articulated louvers flow with the verticality of the corrugated pre-cast blocks, which are horizontally banded between the fenestration but vertical everywhere else. These striking features of the facade do not engage at all with the building's granite, which takes a back seat to the extruded concrete front facade. Furthermore, the granite volume of the building does not register the horizontal or vertical rhythm of the concrete, with the diagonal parapets at the top corners and diagonal vents at the bottom that are formally, rhythmically, and proportionally independent. There is even a shadow line that separates the two. The deeply recessed windows are mysterious, a product of design or function? Were the architects especially aiming for a brutalist form – inspired by leading architects of the previous decades – or are the walls purposefully thick to protect the equipment inside? If so, then why to add windows, the building could easily be a windowless telephone building like 33 Thomas in which it shares many similarities via mass, material, and momentum.

The building was described by Paul Goldberger for the New York Times as overbearing while also being ambitious, “aggressively sculptural and altogether unwelcoming.” (New York Times, 1983) Goldberger was critical of White Plains' automobile-centered urban renewal development, but especially tough on the Telephone Building, stating it “may look intriguing as one passes it in a car, but that makes it like most of the new downtown White Plains, a place that if it works at all, it is from the vantage of the automobile.” (New York Times, 1983) However, the Club Dial, a magazine published by the Woman's Club of White Plains, took a liking to the brutalist behemoth, writing it was cleverly rejuvenated and a fresh new look of a previously boring structure:

“Instead of a variety of different window types, the architect applied one single element, a flat, rectangular concrete slab (like a Venetian blind's blade)creating an intricate appearance by the positional and directional variations of the same element. The dynamic relationship of the horizontal and vertical positions interrupted by omissions at unexpected locations performs like a symphony and dispels the last trace of boredom of the original structure.” (Club Dial, 1974, p.17)

White Plains Public Library. Credit: Mid-Century Mundane.

White Plains Public Library seen behind the Galleria shopping mall construction site. Collection of White Plains Public Library, 1979.

WHITE PLAINS PUBLIC LIBRARY

Date: 1974

Architect: Gibbons, Heidtmann, and Salvador

Address: 100 Martine Avenue, White Plains NY

Use: Public Library

White Plains Library architectural rendering. Credit: Damiano Barile Engineers, P.C..

On the other side of the Galleria from the Telephone Building, in the shadow of the courthouse, is the White Plains Public Library. By the sixties, the White Plains Library had outgrown its small brick structure, designed in 1908. As part of the urban renewal development’s civic center, the town was promised a new library that would be four times the size of the old one.

When it opened in 1974, the $6.2 million library was one of the first public urban renewal buildings completed. Cast in concrete and two stories high, the building is rectangular and horizontal, with vertical concrete panels giving the facade a linear rhythm.

“The impressive vertical thrust of the courthouse creates a dramatic contrast with the horizontal simplicity of the library, guarded by the massive silhouette of the Telephone Company Building. Despite their completely different individual concepts, the predominantly linear rhythm of their external appearance connects them to the exciting cityscape. The Courthouse and Library represent a happily counterbalanced architectural marriage that could not exist effectively alone.” (Club Dial, p17)

Sources:

Club Dial. February, 1974.

Goldberger, Paul. REDEVELOPMENT IN WHITE PLAINS MIXES SUBURBAN AND CITY STYLES; An Appraisal. The New York Times, July 12, 1983.

White Plains Public Library Collections.

Himmelfarb, Ben. Local History: Urban Renewal Collection. White Plains Library.