MACY'S QUEENS PLAZA

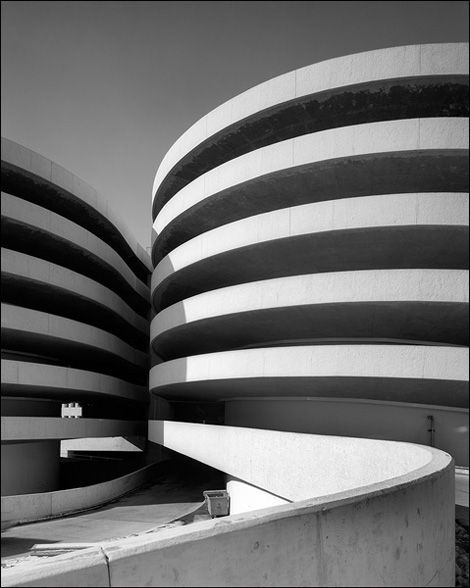

Macy's Queens Plaza exterior view and floor plans. Credit: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.

Date: 1965

Architect: Skidmore Owings & Merrill

Address: 88-01 Queens Boulevard, Queens

Use: Shopping Center, Parking Garage

Macy’s Queens Plaza is automobile-oriented modernism of the first degree, illustrating the rise of suburban shopping malls in America and their penetration of urban centers by the mid-sixties. The Macy’s store in Elmhurst Queens was the 51st department store for the company, founded in Manhattan, that was quickly becoming a nationwide chain. The circumferential structure was built on a five-acre site bordered by Queens Boulevard, Justice, 55th and 56th Avenues, next to the newly constructed Lefrak City apartment complex.

By the early sixties, Macy’s was on track to build their new 326,500 square-foot Queens store, and started clearing the site which was mostly empty, except for a few homes. One homeowner, Mary Sendek, who owned a small house on a 169 x 52 foot lot refused to sell. Macy’s offered her as much as $200,000 (more than $1.5 million in today’s dollars), over five times the value, but Sendek refused to even sell her backyard. Despite this setback in Macy’s development, the company proceeded with the department store’s construction, building it around Mrs. Sendek’s property. However, this forced Macy’s to forfeit a more elaborate entranceway, instead, creating street-level entrance doors along the perimeter of the exterior. Fifteen years after Macy’s Queens Boulevard opened, in 1980, Mrs. Sendek passed away, and her children sold the house to a developer who demolished it to build a small strip mall.

Mary Sendek’s house (second to right in top photo) was the only house to remain on the site after Macy’s was built. The owner refused to leave even after offers five times the value of the property. The property would eventually be sold in 1980 and redeveloped into a two-story brick shopping center. Credit: forgotten-ny.com.

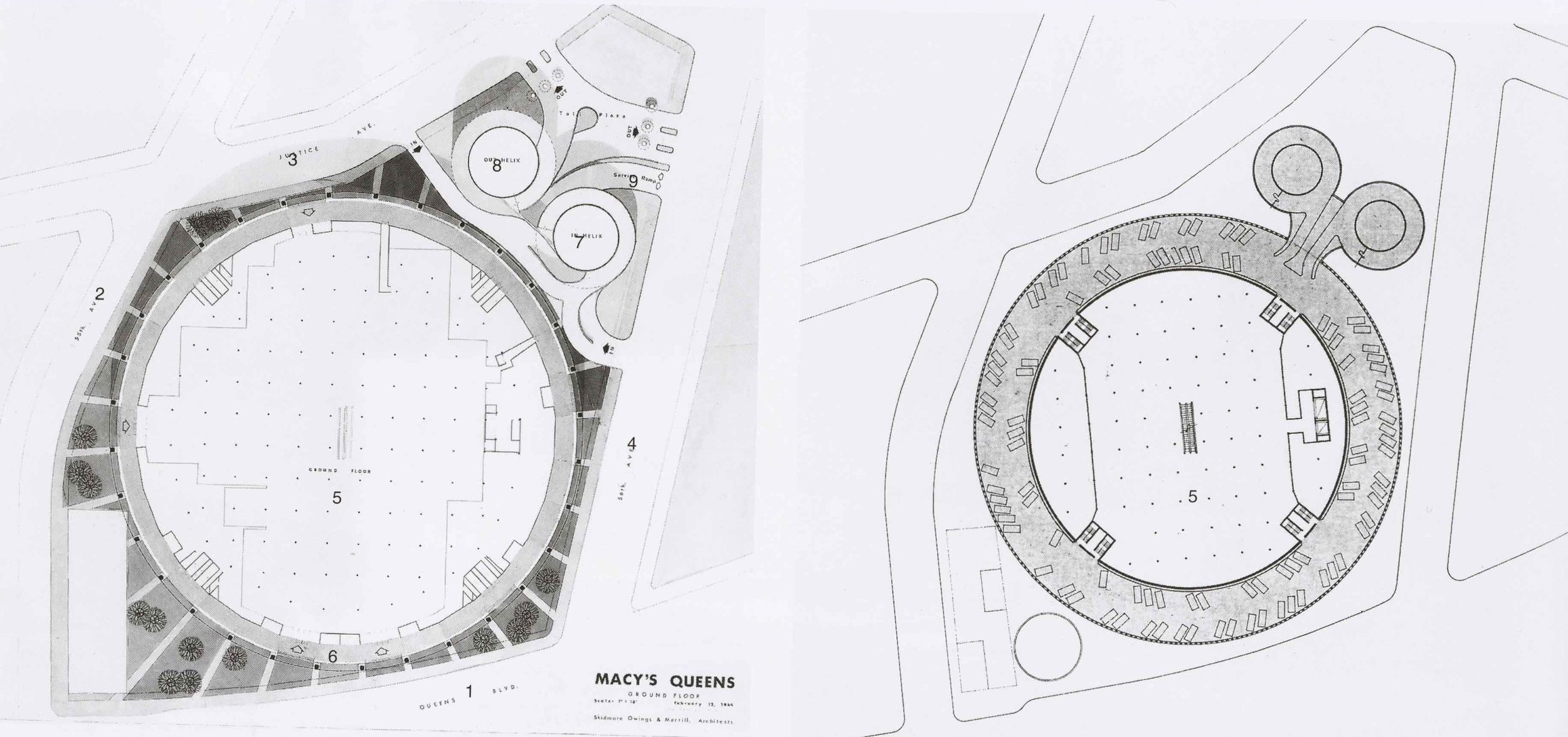

Macy’s Queens Boulevard was designed to accommodate the automobile, making it easy to access the store, providing plenty of parking spaces. The location is also a prime spot for car traffic, just west of the Long Island Expressway and on Queens Boulevard, two major traffic arteries. Designed by William S. Brown of Skidmore Owings & Merrill, the department store incorporated a parking garage into the 426-foot-diameter structure. Out of the five designs, S.O.M proposed to Macy’s, this was the only one not to include a detached garage. An underground parking lot was not possible at the site due to the high water line. The store is located in the core of the structure, with the five levels of exterior rings and the roof providing parking for 1,250 cars. This offers customers the ability to easily travel to the store from their car without the use of a street level or detached parking lot. Two ramps at the back of the structure provide access to the parking levels from the street. The facade was created with poured-in-place concrete, which was then sandblasted to expose a coarse white mass. It is perforated to allow natural ventilation in the parking lot. A relentless grid of fenestration wraps the entire building – no glass, just ventilation holes – to provide light and air to the parking garage within.

Inside the five parking rings are three sales floors with 270,000 square-feet of space, the largest being the ground level, which extends beneath the first garage level and is accessible from the sidewalk outside. The remaining area provides space for an internal shopper's arcade with display windows.

Macy's sectional, showing the five rings of parking and the option to expand three more levels. Credit: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.

Macy's ground floor site plan (left) and parking (right). Credit: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.

While Macy’s design was innovative for its time and succeeded at introducing the automobile-centered shopping mall of the suburbs to the urban density of Queens, less than a decade after Macy’s Queens Boulevard opened, Queens Center, a larger, more modern and centrally located mall would open just blocks away. In 1996, even Macy’s would relocate to Queens Center, with the former site now housing various stores and a Macy’s furniture gallery.

SOM’s design was elemental with regard to its massive circular form in a way that few architects ever have the chance to achieve. The evenly spaced concrete piers - massive in size - form a “pedestrian” arcade at ground level that relates not to the scale of the hypothetical pedestrian user but to the surrounding cars and massing of the building. The design expresses similarities to Bellevue’s “New Building” in its geometrical elementalism and lack of natural light but does not shallowly pander to stylistic trends of brutalism. The structure's facade and form are completely in line with SOM’s brand of hardline modernism of the 1960s and ditches interior natural light for more well thought out reasons than Bellevue. By wrapping the department stores with parking levels, the structure accurately reproduces the experience of suburban shopping by creating a near-streetside condition, allowing patrons to park within feet of the store’s entrances without having the cars visible from the surrounding streetscape. While the type of car-centric urbanism that this building represents proved to be harmful to cities like New York, SOM did a great job at both achieving a highly functional building that clearly demonstrates creative possibilities for these intentions while giving the whole project a powerful, hardcore form that ties the neoclassical origins of elemental modernism to the post-war automobile age.