ENDO PHARMACEUTICALS BUILDING

Library of Congress, 1965.

Endo Pharmaceuticals Building

Date: 1962

Architect: Paul Rudolph

Address: 1000 Stewart Ave, Garden City

Use: Office

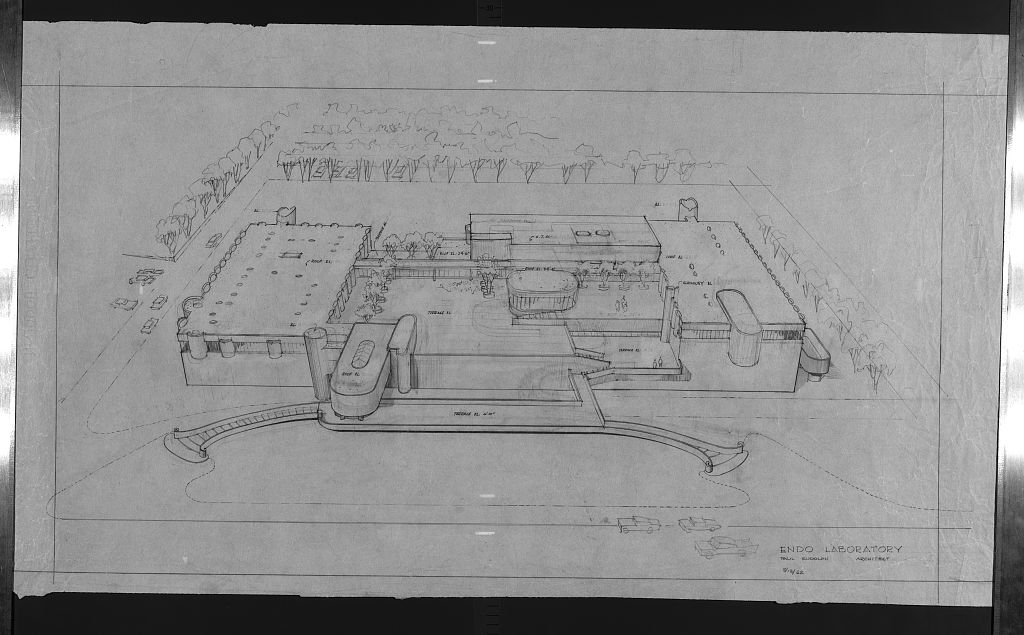

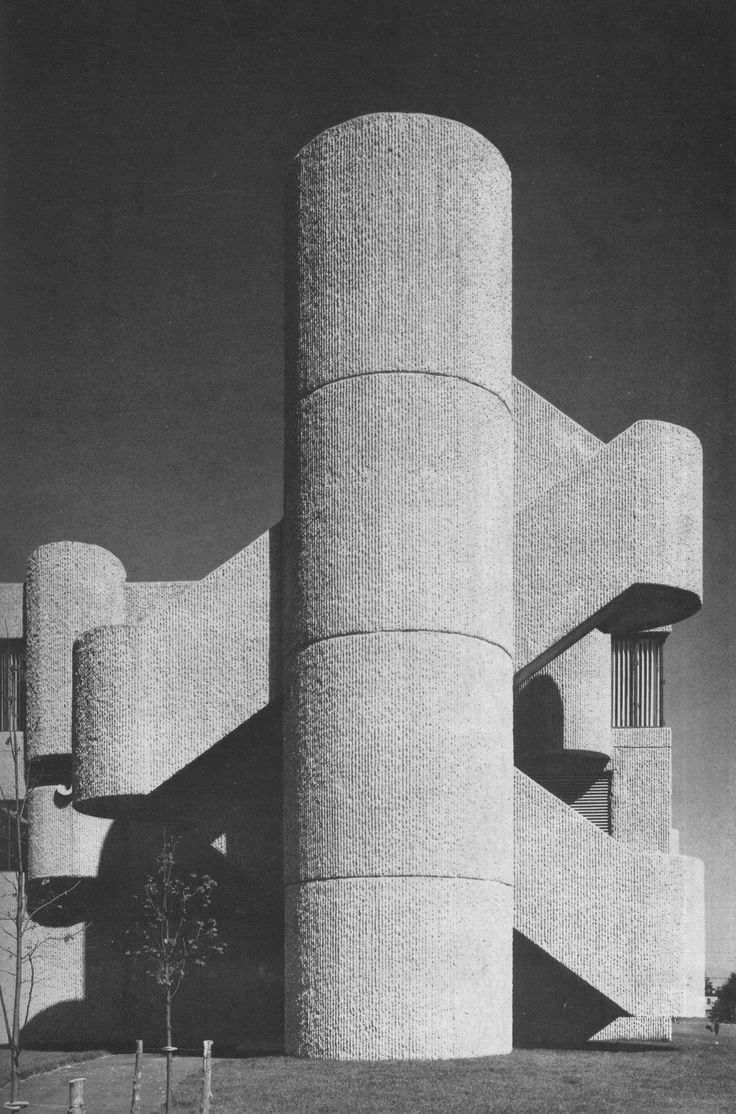

Paul Rudolph’s Endo Laboratories is a highly expressive machine choreographing the most effective use for its client. Rudolph expresses Endo’s functionality, then adds an additional layer that is sculptural – a material expression to create art. Endo merges interlocking volumes and forms to articulate the spatial specificity necessary for the highly precise program needed for manufacturing pharmaceuticals. While some of the interiors appear generic, such as open office or production floors, they represent the specifically calibrated spaces for operation and production. Turrets and other seemingly arbitrary elements reveal themselves to be expressions of function - housing activities necessary to the efficiency of the building’s program. Rudolph’s baroque exuberance comes through most clearly in the curving staircases; one at the guest entrance, and one leading to the pod-like cafeteria that is raised above the roof garden. Turrets, which house the functional systems from seating alcoves and air intake valves are distinctly Rudolphian in the way the building explodes out from its orthodox envelope. This distinguishes it from the classical Miesian brutalism of many of the other buildings in this survey, made possible because of the building’s open site plan outside of the city.

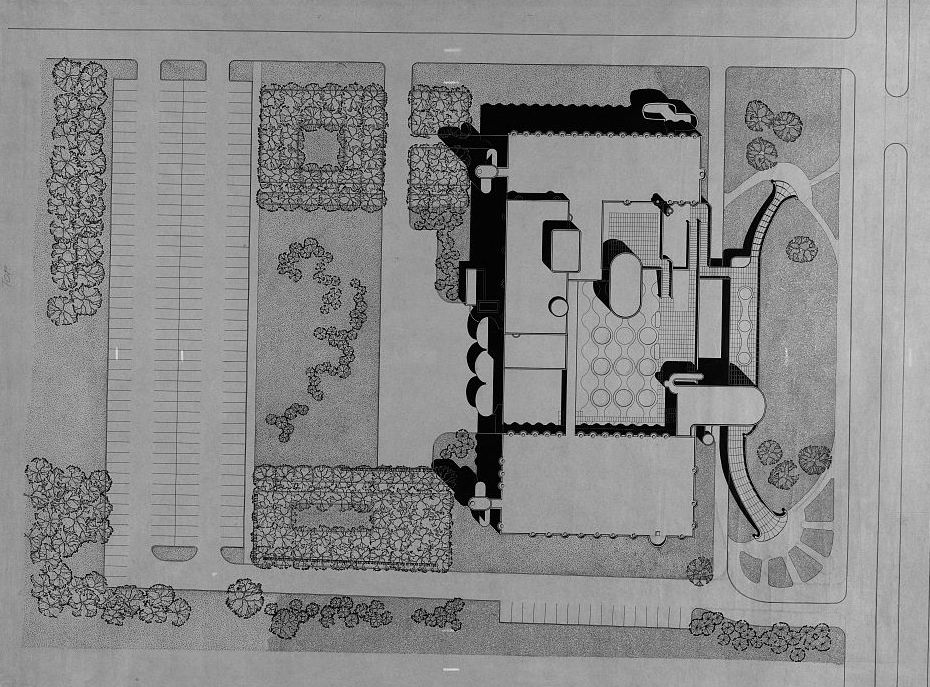

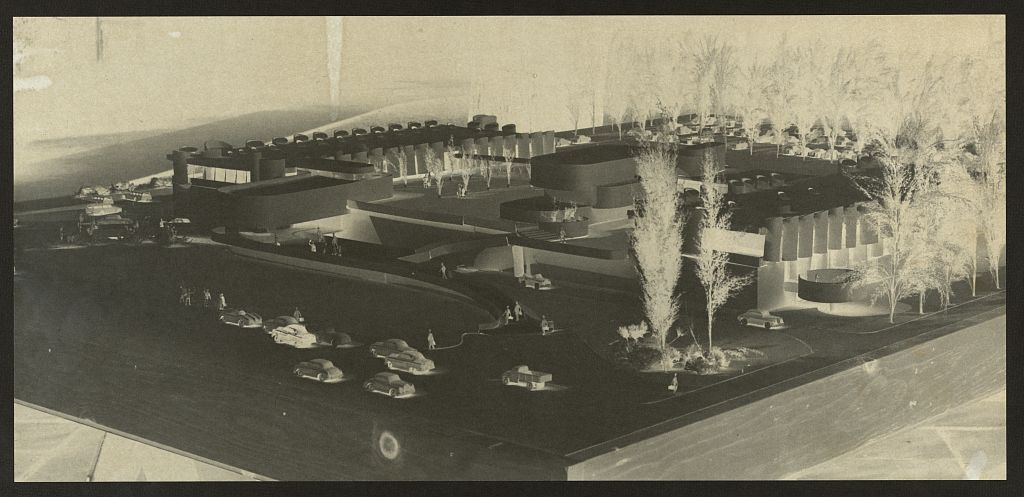

Endo Pharmaceuticals’ headquarters in Garden City, Long Island was built between 1962 and 1964 on an eight-acre site at a cost of $5 million. Designed by Paul Rudolph, the complex is made up of the 165,000 square-foot turreted main building at 1000 Stewart Avenue and the smaller 25,000 square-foot rectangle at 500 Endo Boulevard, which was constructed several years earlier. Endo Pharmaceuticals commissioned Rudolph to design a state of the art facility for the company, which was previously located on a smaller site in Queens. Strategically located on a site overlooking the Meadowbrook Parkway so the company's headquarters could establish a presense, Endo’s executives envisioned an iconic building that would represent the company’s identity.

(Paul Rudolph’s Fluted Concrete Buildings. Concrete Construction, April 01, 1965.)

Dubbed the “Fortress for Pharmaceuticals,” the castle-like structure featured Rudolph’s iconic corduroy concrete facade. Rudolph’s béton brut (raw concrete) departs from the board-marked concrete of Corbusier in that it does not articulate the texture of the boards but serves the constructed signature materiality of the corduroy form. The concrete foundation supports a structural steel skeleton that is clad in concrete inside and out. The cast in place ribbed concrete was originally developed for Rudolph’s Yale School of Architecture, which was completed the year before. To create the corduroy appearance, Rudolph designed specialty plywood fins which established a mold for the concrete to be poured into. After the concrete dried, the plywood formwork was removed and the fins were chipped away with a hammer to reveal the rough ribbed texture. The various stages of pour are visible today in the concrete's horizontal banding. Unlike the Yale building, Rudolph improved on this method and was able to use it on the curved surfaces of the structure’s interior and exterior. Because the building was being used for laboratories, it also required smooth concrete interiors. Rudolph’s concrete method cost only slightly more than conventional concrete, averaging $26 per square foot. The method is described in more detail by Concrete Construction,

“On a plywood backing, trapezoidal fins 2 inches deep by 1 and one-half inches at the base by one-half of an inch at the top are nailed in place. They form a regular pattern, the space between the fins being equal to the width of the fins. These forms are paced as usual for any concrete wall. A stiff mixture of concrete with about a 2 inch slump and 1 to 1 and one-half inch aggregate is then placed. After removal of the forms, the fins are broken off with a hammer, thus exposing the aggregate. Often the aggregate breaks along with the concrete, and the interior tones of the aggregate are exposed. This method does more than decorate an otherwise smooth surface. Often used both inside and outside, it eliminate the necessity of any further finishing of the concrete.” (Concrete Construction, April, 1965)

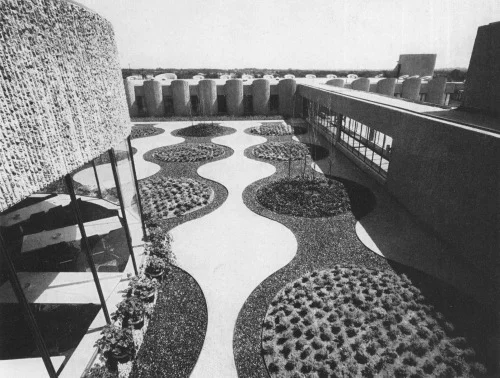

Roof Garden and Cafeteria (on left)

The three-story building features several hollow turret-like cylindrical forms that undulate along the facade, giving the building the appearance of a castle or fortress. In Rudolph's design, functional articulation moves beyond function to sculpture. With Endo, Rudolph externalized the functional elements that most architects bury inside buildings; the stairs, vents, mechanical systems, executive desk alcoves and air ducts, freeing up space to create a more open floor plan. The turrets are topped with a translucent material that acts as a skylight since the building’s windows are slender and limited, interrupted by the turrets. Along the building's roof is a garden, which is visible from the cafeteria level.

Visitor entrance

The structure’s primary use is pharmaceutical manufacturing, and the building is divided into three major sections; production, administration, and research. Upper floors are devoted to offices and research labs, with manufacturing below and packaging on the ground floor. Like the Yale building, the interior floors are black slate with orange carpet (recent renovations have removed the orange carpet.) Employees enter the facility from the rear where the large parking lot is located, but visitors are met with a more prominent entrance – two large staircases that rise to the second story of the structure. The reception area is one of the few glass enclosed interiors and looks out onto the roof garden.

When the building opened in 1964 it was awarded the "Concrete Building of the Year" by the Concrete Industry Board, among other awards. Overseas Rudolph's design for Endo was widely reviewed in architectural journals. European critics were more understanding of Rudolph’s intent, viewing it as one of the closest American interpretations of Corbusier.

Not everyone appreciated Rudolph’s modern design. The complex was clearly visible to motorists on the Meadowbrook Parkway who were not as accepting of Rudolph’s artistic license. The Long Island Parks Commission responded by planting nine large evergreen trees in front of Endo, blocking the view from the Parkway. Although they publicly stated the trees were not placed to obstruct the view of the complex, it was clear the intention was to hide it from local commuters, many of whom considered it an eyesore.

New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable covered the controversial tree placement but widely praised Endo in her review, writing it was the strong character of the building that elicited such strong reactions. Huxtable went on to name the building “one of the best” in the New York Area.

“There is a heady effect of rugged exotic beauty… efficient and economical, and the exhilarating result is a definitive argument for art and excellent in the practice of construction. Buildings like this are the real legacy of Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier… a dynamic, evolutionary synthesis of innovations of the master's… representative of the best and most vital construction being done today.”

Rendering of the remodel (PRWeb , 2006)

Just five years after the plant opened, Endo was sold to E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Co., who continued to use it as a pharmaceutical plant under the subsidiary Endo Pharmaceuticals for the next several decades. In 2005 Metropolitan Realty Associated LLC (MRA) purchased both buildings on the site and underwent an award-winning, multi-million dollar renovation in 2007, adding windows, landscaping, new building systems and parking. The building was converted into a mixed-use facility, housing various companies including Nassau Community College and the headquarters of Lifetime Brands. Unlike other Rudolph buildings which have been demolished, or are facing demolition, the recent renovation and full occupancy ensure Endo’s permanence in the area. Six years after MRA purchased the complex for $7.4 million they sold the property to Angelo Gordon & Co. for $39,250,000, making it the most expensive commercial sale on Long Island that year.

Sources:

Dixon, John Morris. Fortress for Pharmaceuticals. Progressive Architecture 45 (November 1964): 168, 170.

Stern, Robert A.M. New York 1960. 1077, 1079

Huxtable, Ada Louise. Design of Garden City Plant Stirs Extreme Reactions. The New York Times, 9-20-1964

Paul Rudolph’s Fluted Concrete Buildings. Concrete Construction, April 01, 1965.