ROOSEVELT ISLAND

Roosevelt Island is a 2.5-mile long sliver of land in the middle of the East River between Midtown Manhattan and Queens totaling 147 acres. The island was first known as Blackwell’s Island, named after the Blackwell family who farmed the land before selling it to the city in 1825 when it was then used for various public facilities over the next century; a penitentiary, smallpox hospital, cemetery, and insane asylum.

Goldwater Hospital, Roosevelt Island, 1939.

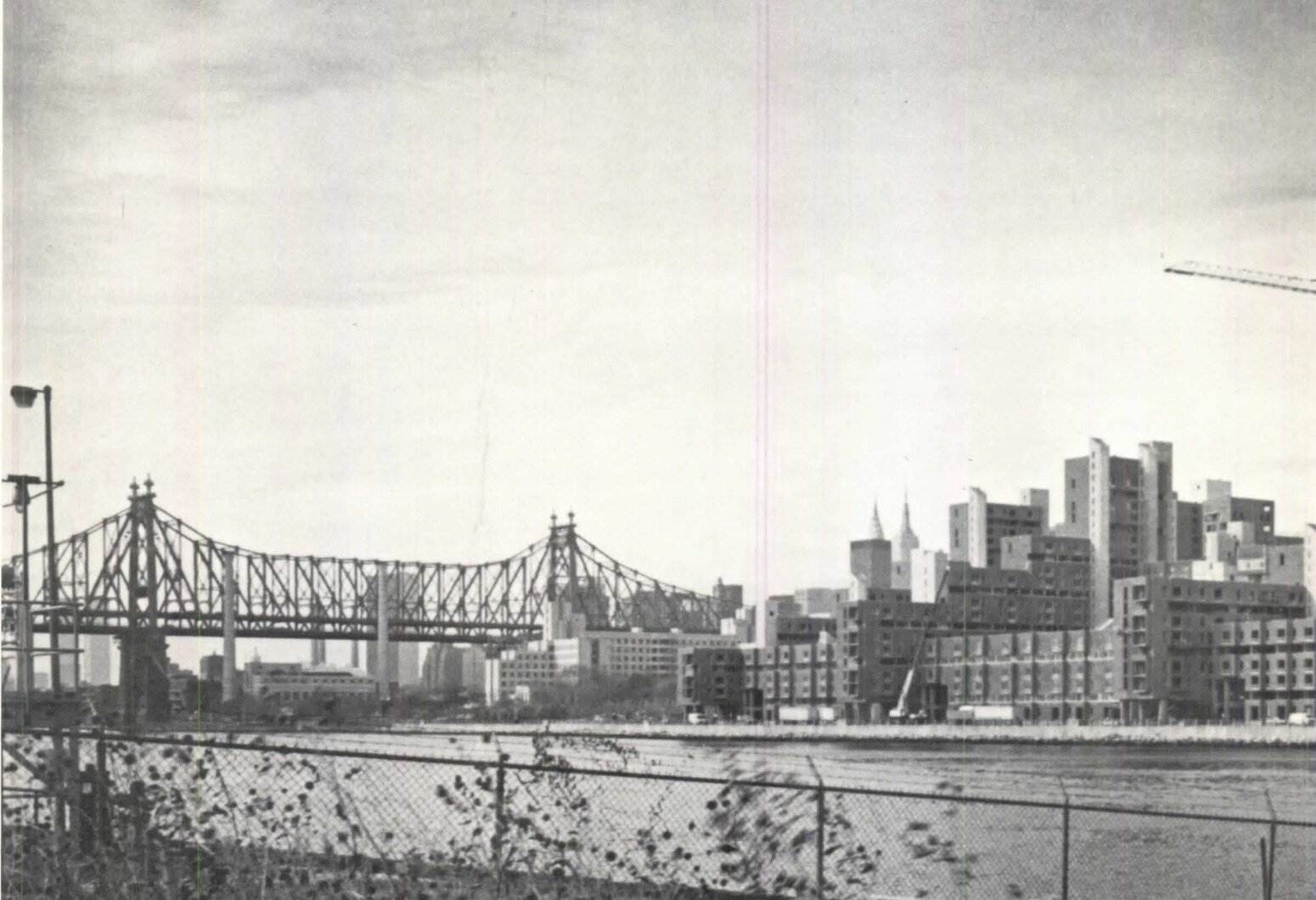

The city would drastically transform Roosevelt Island in the mid-20th century, following the construction of the Queensboro Bridge, which opened in 1909 and passed over the island without providing access to it. In 1921 the island was renamed Welfare Island after the public hospital located on the southern end. Automobile and trolley transportation was first introduced with the opening of a vehicular elevator from the Queensboro Bridge in 1930. Over the next three decades, two large hospitals opened and in 1955 the Welfare Island Bridge was constructed, connecting the island with Queens and opening it up to more vehicular traffic.

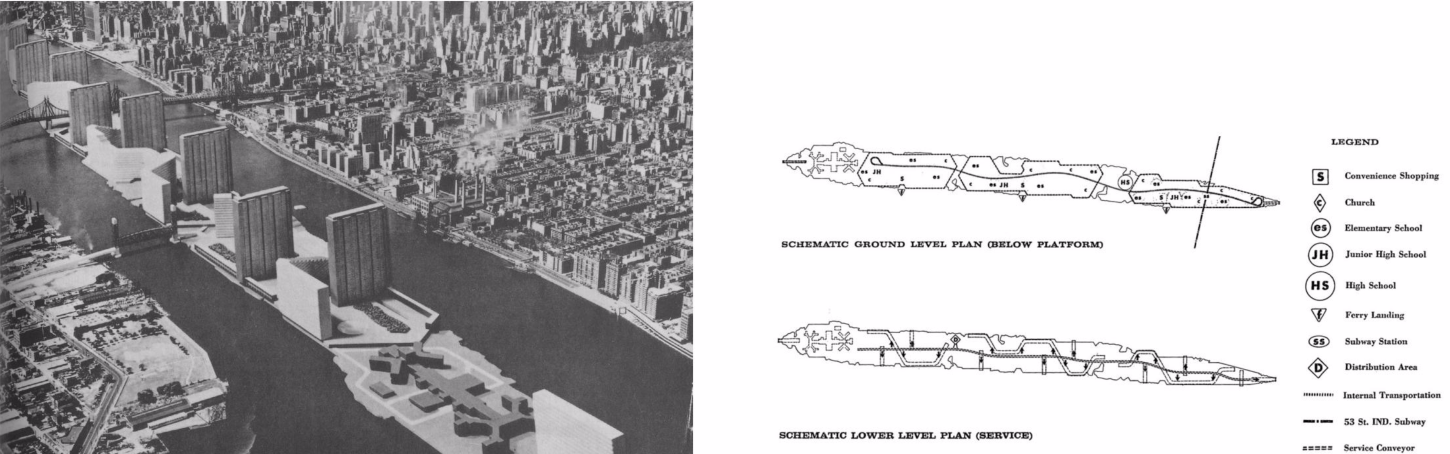

In the 1960s planners and politicians started eyeing Welfare Island for a mixed-use masterplan. Urban renewal projects were transforming neighborhoods across the city and Welfare Island’s close proximity to Midtown and public designation made it a prime candidate for development. In 1961 shopping mall pioneer Victor Gruen proposed constructing a platform 22-feet above the island for a residential community of 70,000 people with schools, stores, public facilities, and housing, all connected by air-conditioned malls. The plan, which would have renamed Welfare Island, East Island was never realized, partly because of competing proposals to turn the island into a park and because the city was wary of giving such a large tract of land to one developer. East Island was just the first of many proposals that were considered during this period, none of which gained significant political favorability. One far-fetched proposal included digging up bodies in Queens and Brooklyn cemeteries and reburying them on the Island to free up space in the two Boroughs. Other ideas included linking the island to Midtown via landfill and multiple causeways, funneling the East River and shipping traffic through a narrow canal. The most significant development was the decision to connect the island to the subway system, with a station just north of the Queensboro Bridge in 1963.

Victor Gruen's platformed proposal for Roosevelt Island, 1961

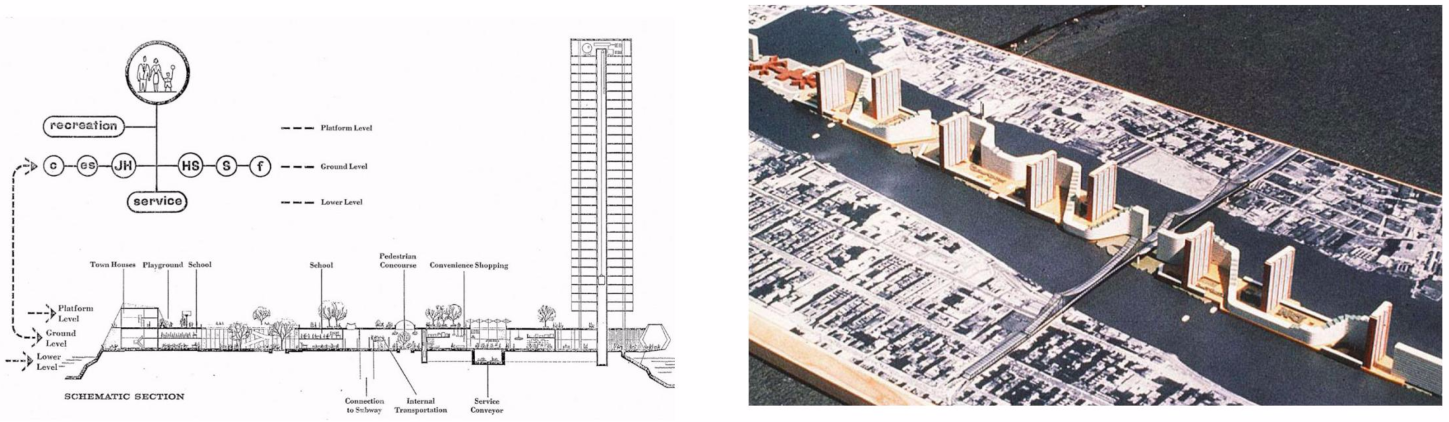

Philip Johnson, John Burgee, New York State Urban Development Corporation, The island nobody knows, 1968. View the full report here.

In 1966 Mayor Lindsay officially announced the city’s intention to develop the island with the first step of demolishing forty five condemned hospital structures. In 1969 the newly established New York State Urban Development Corporation (UDC) issued a 141-page report analyzing the different options for the island. They proceeded to sign a 99-year lease for the land and brought in architects Philip Johnson and John Burgee to design an ambitious masterplan with housing for 20,000 new residents. Johnson and Burgee called for a mixed-income, automobile-free community planned around landscaped plazas and promenades utilizing the picturesque river and skyline views. While the development would have commercial and civic buildings – a public school, daycare facility, parking garage, office space and a hotel – the large majority of space would be used for apartment buildings of varying shapes and sizes. The area was split into two “towns,” Northtown and Southtown, of which there were nine zones, five parks, and four building lots. This was done to preserve the vistas from the island and to avoid long slab-like developments running the length of the island, as seen in the Gruen Plan. The only street, Main Street, would run north-south reserved only for emergency vehicles, minibuses, bicycles and necessary deliveries and would be the location of commercial and public facilities. Instead of cross streets, pedestrian walkways would bisect the island between buildings. Certain existing island buildings such as Blackwell House and the Lunatic Asylum would be landmarked and preserved. The masterplan was approved in October 1969 and the UDC immediately lept into action, hiring architects for the housing, garage, commercial facilities, infrastructure, and parks.

Johnson & Burgee's Roosevelt Island masterplan. Credit: The island nobody knows, 1968. View the full report here.

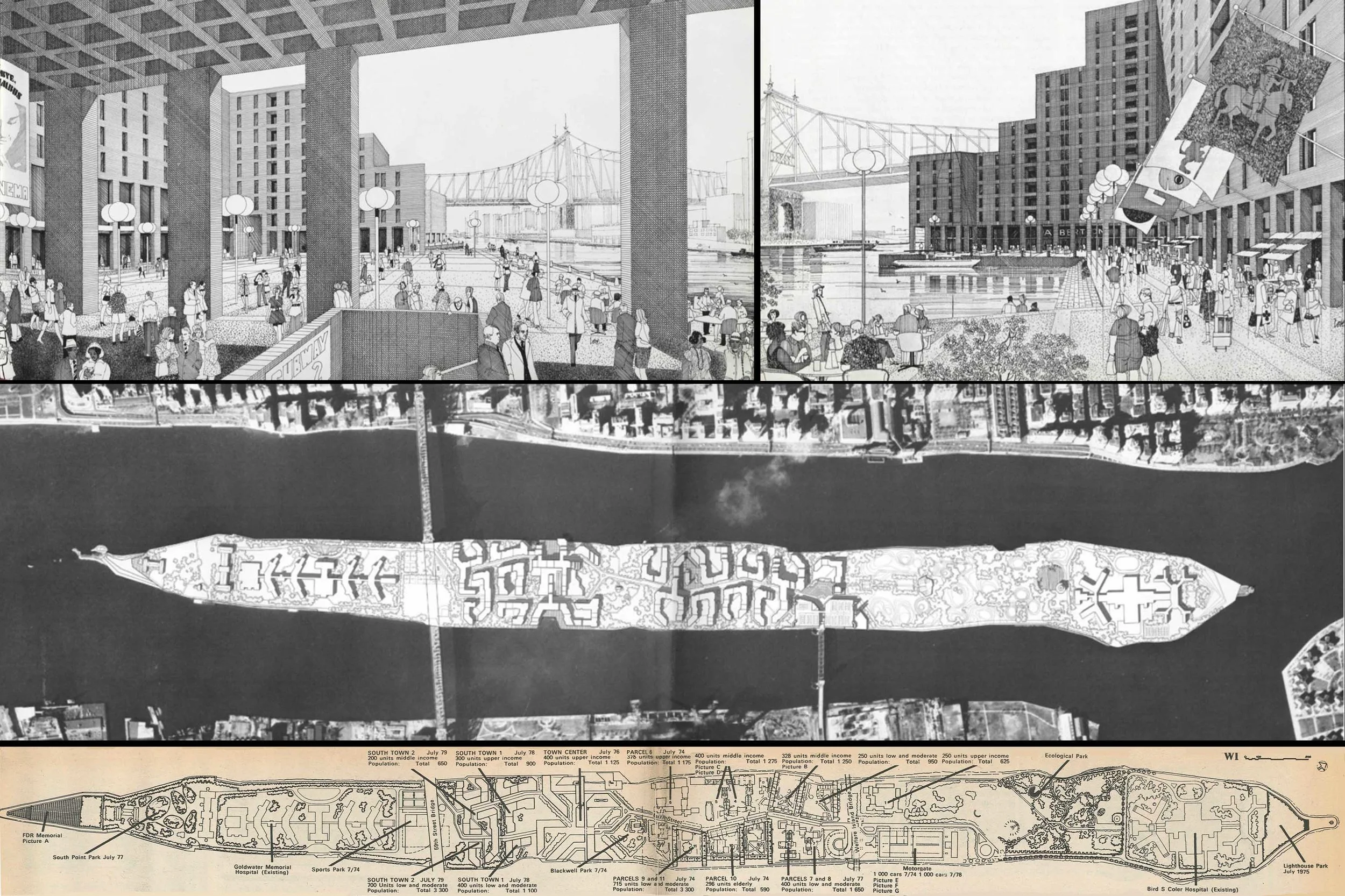

In 1973 as construction was underway Mayor Lindsay renamed Welfare Island Franklin D. Roosevelt Island, unveiling plans for a monument and park at the southern end of the island named “Four Freedoms Foundation Monument to President Roosevelt.” Designed by Louis Kahn, the monument was a 780-foot-long triangular site created by landfill from the new subway tunnel, strategically positioned directly across the river from the United Nations headquarters in Midtown. Four Freedoms would face delays and not open until 2012. The 63rd street subway tunnel connecting Roosevelt Island to the system would not open until 1989.

The first phase of construction commenced in the summer of 1971 with 2,138 units of housing for 5,000 residents in four apartment buildings, along with streets, sewers and commercial space. Kallmann & McKinnel were hired to design Motorgate, a parking garage with a firehouse, post office, full-sized supermarket and retail. The housing developments Rivercross Apartments and Island House, designed by John Johansen with Ashok M. Bhavnani were completed in 1975. Johansen & Bhavnani’s Rivercross and Island House buildings were reinforced concrete structures clad in cement-asbestos panels, stepped up from the Manhattan side of the East River, housing 850 middle- and upper-income families. Across Main Street was Sert, Jackson & Associates’ Eastwood and Westview Apartments, a Mitchell-Lama development, which housed lower- and middle-income families on a six-acre site that was completed a year after Rivercross and Island House.

Sert was one of Europe’s leading modernists and a highly influential figure in post-war modernism, both in architecture and planning. Before coming to the U.S., Sert worked under Corbusier and co-founded the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM). As Dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design during the 1950s and 60s, Sert helped to spread the styles and ideas of Corbusier, Team X, and European Late-Modernism across the Northeastern U.S. Critics claim that his work was too reliant upon Corbusier or that he represented disproven orthodoxies of modernist ideology, but his work on Roosevelt Island, like his projects in Cambridge, deliver a type of late modernist Architecture, that like Corbusier, bridges the worlds of orthodox CIAM theoretical modernism with an avant-garde artistic sensibility. This varies from the formalist approach that we know in the U.S. thanks to Rudolph, Johnson, SOM, Stone, and Saarinen.

EASTWOOD

(ROOSEVELT LANDING)

Date: 1976

Architect: Sert, Jackson & Associates

Address: 510 - 580 Main Street, Roosevelt Island

Use: Residential

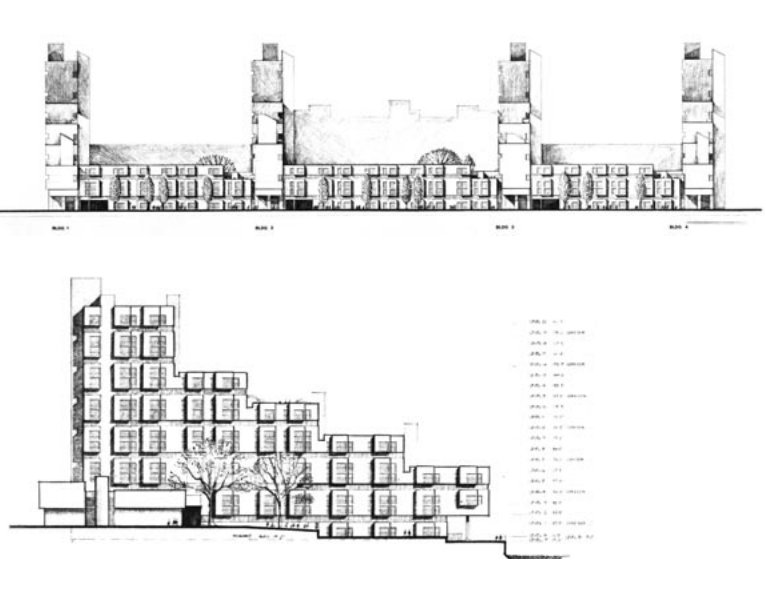

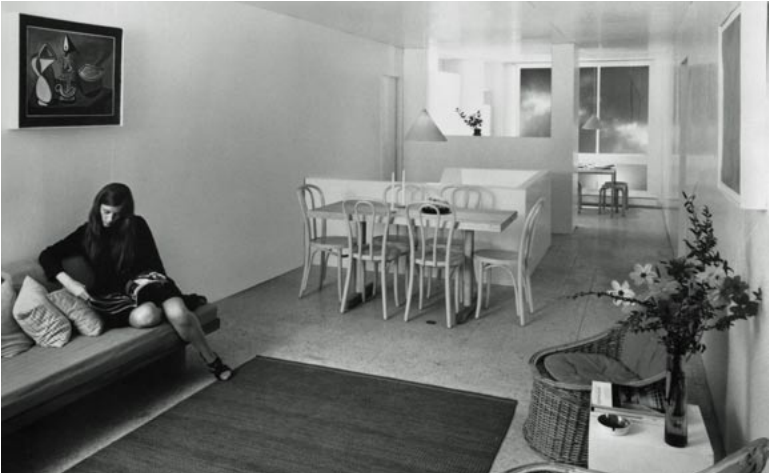

Sert’s apartment buildings Eastwood and Westview are two of the most interesting and innovative housing developments of the period. At 1,003 units, Eastwood is the largest residential complex on the island made up of ten connected buildings, stepped back from the water, forming three courtyards, each containing their own community facility; a school, senior center, and outdoor amphitheater. The courtyards are enclosed on all four sides, walled off from the waterfront except for a few open-air passageways that access a promenade along the river. Sert positioned the lowest slabs along the water, opening up the panoramic views from the rising towers, similar to 1199 Plaza across the East River in Manhattan. This was a compromise from Johnson’s original master plan that called for the courtyards to open up to the waterfront, unobstructed. Johnson’s masterplan pressed the need for a human scale, with buildings not exceeding ten stories, however, the UDC analysis determined the heights would need to increase to up to 22 stories to meet the required density. Sert and Johansen’s buildings were able to retain Johnson’s human scale by gradually stepping the 22 story east-west sections back from the river, preserving the water views and capping the longer north-south portions that followed Main Street to seven stories, creating a concrete canyon along the narrow street. Sections of the building along the river promenade were raised to create an arcade, along with openings into the courtyards.

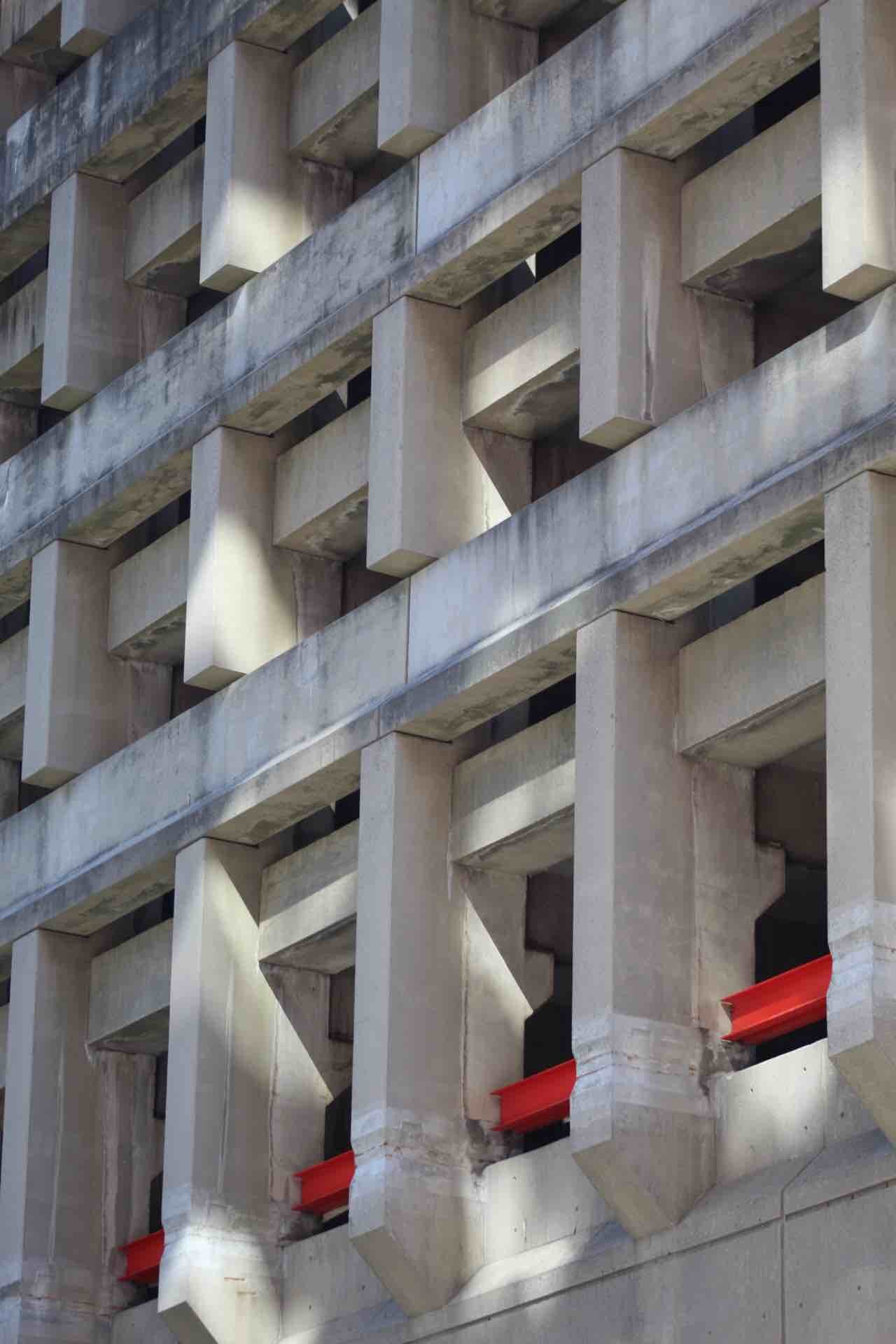

Along Main Street, the buildings form a pedestrian arcade, raised above the sidewalk by smooth poured concrete columns. The facade is comprised of precast board-formed striated concrete panels, resembling Paul Rudolph’s iconic corduroy texture. Sert left the mortar lines on the facade visible, giving the panels a tiled pattern. The elevator shafts provided visual anchors for the buildings – a smooth, lighter concrete with small windows illustrating the skip-stop elevators that stopped only every third floor.

MOTORGATE GARAGE

Flickr user zkorb

Date: 1974

Architect: Kallmann & McKinnel

Address: 688 Main St, Roosevelt Island

Use: Parking Garage

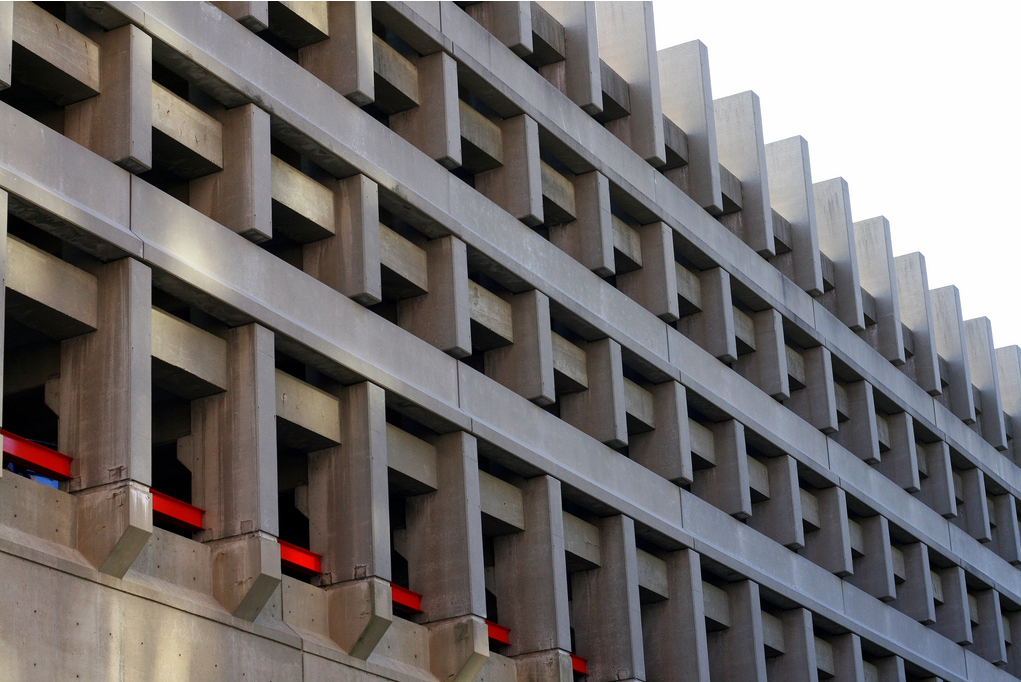

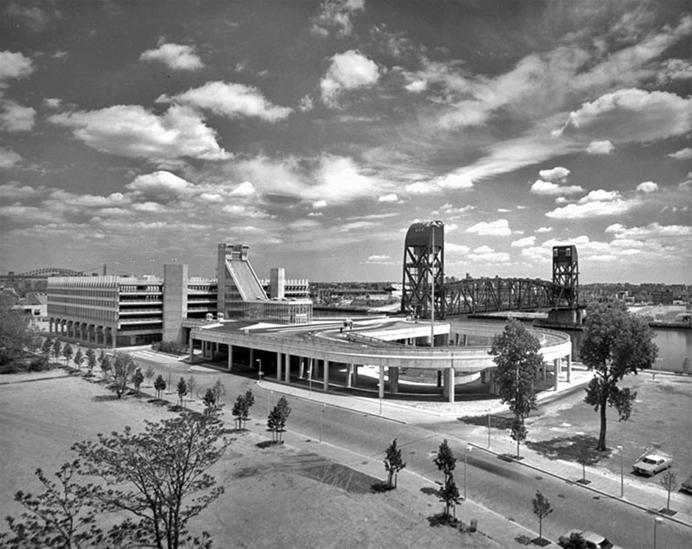

Roosevelt Island’s utopian vision was centered around the Motorgate parking garage. Designed by Boston City Hall architects Kallman & McKinnel, the garage was intended to absorb the load of automobile traffic to the island, creating New York City’s only car-free neighborhood. With capacity for 1,000 cars, (then increased to 2,600) Motorgate was established to hold vehicles for all island residents, their visitors and employees of Roosevelt Island institutions and businesses. Johnson and Burgee’s masterplan proposed restricting all traffic on the island with the exception of deliveries, construction trucks, ambulances and personal emergencies. Motorgate was constructed at the base of the Roosevelt Island Bridge, the sole vehicular connection to the island, funneling all traffic into the garage ensuring the 38-foot-wide Main Street would be restricted to pedestrians. In 1975 a pneumatic trash collection system was installed to deliver all waste to a central collection point, making garbage trucks obsolete. The concrete-framed six-story structure was an adaptation of the architect’s work on Boston’s City Hall (1968) with influences from Paul Rudolph’s Temple Street Parking Garage in New Haven.

The UDC had hoped to create a livable neighborhood in the city that could compete with the growing suburbia, allowing residents open space and a parking spot, while still having a walkable community with close proximity to Midtown Manhattan.

On the lower level, the garage incorporated a post office and grocery store, helping to open it up to the surrounding urban fabric and making it more inviting to pedestrians. These commercial additions also solidified the site as the civic center of the new planned community.

Sources:

DOCOMOMO, Touring Roosevelt Island – 2011 DOCOMOMO Tour Day recap. November, 21, 2011.

Phillip Johnson, John Burgee, New York State Urban Development Corporation, The island nobody knows. 1969.

Josep Lluis Sert, The Josep Lluis Sert Collection: An Inventory. Special Collections, Frances Loeb Library, Harvard Design School.

Jane Silverman. Will New York Blunt Its 'Extraordinary Tool' For Housing Development? AIA Journal, 1975. P.28

David Turturo, Roosevelt Island Bends to Market Pressure. Metropolis, September 4, 2014.

David Turturo, New York’s Twilight Zone: Inside Roosevelt Island’s Concrete Townscape. Metropolis, August 4, 2014

Stern, Mellins, and Fishman, New York 1960. 1995, 641-659.

Urban Development Corporation, POLICY AND DESIGN FOR HOUSING Lessons of the Urban Development Corporation 1968-1975.

Mason, Betsy. New York City’s Trash-Sucking Island. Wired, 2010.